|

Dear lovely readers,

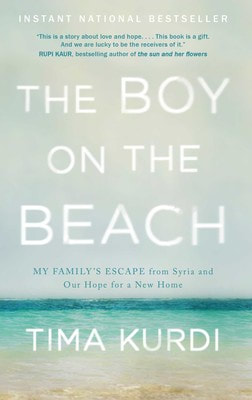

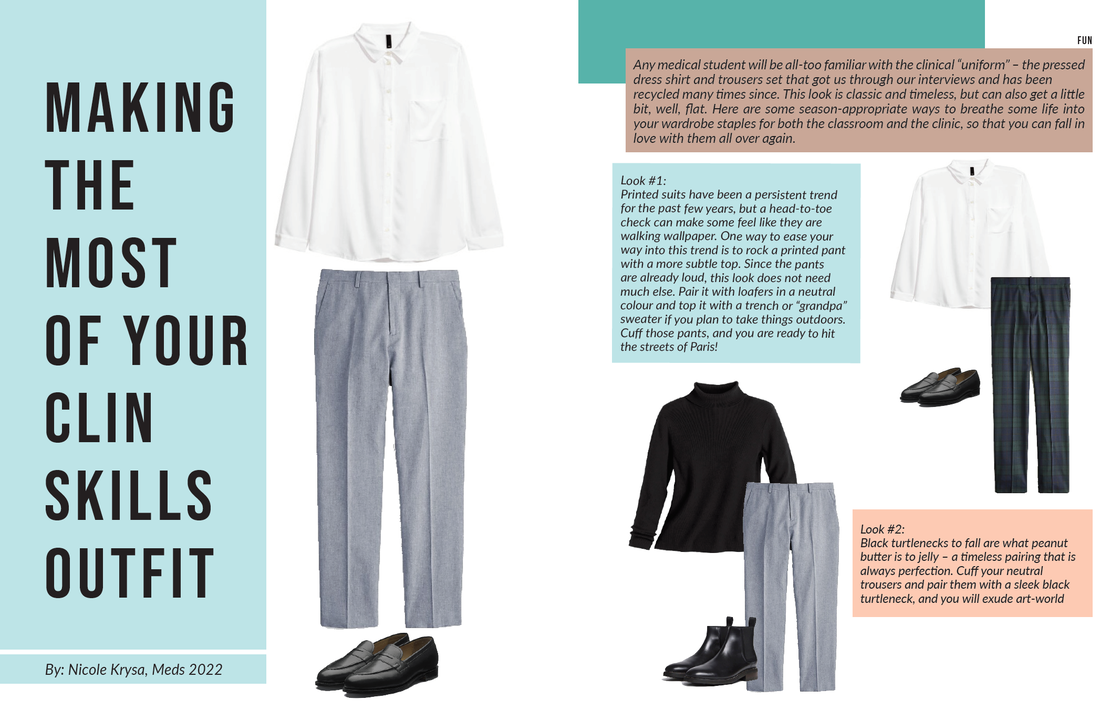

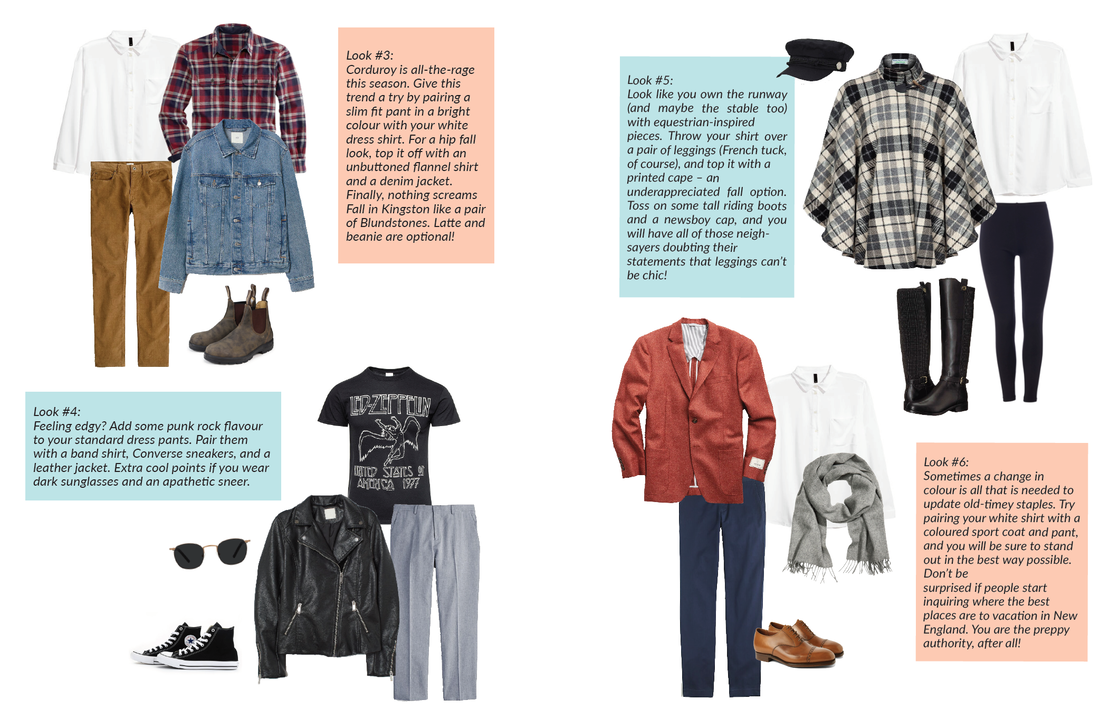

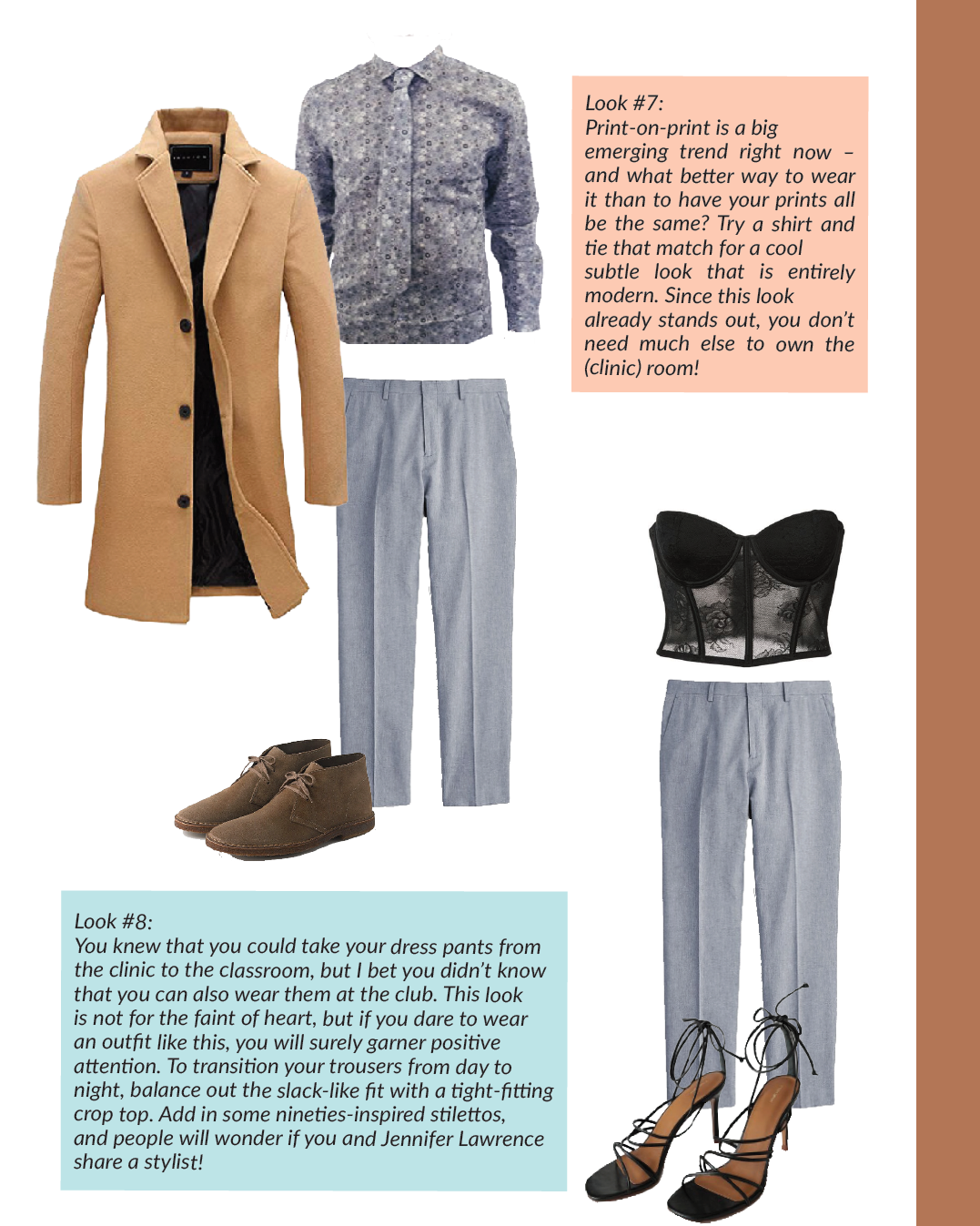

Welcome to our Growth Issue. We are so thrilled that you have decided to pick up a copy of the QMR and give it a read. We are very proud of the content that our entire team (writers, editors, layout, and artists) have brought forward to our first issue of the year (and our first issue as Editors-in-Chief)! For this issue, we challenged the Queen’s Medicine community to interpret the theme of Growth in various ways. Given the dynamic spread of talent in the QMed community, it should come as no surprise that the results were wide-ranging. In the Growing Costs of Healthcare in Canada, Victoria Lee-Kim takes a critical eye to the economics of providing care, and asks what we as medical learners should know, and how this financial climate might impact us as practicing physicians. Emma Spence meditates on the process of growth and development in all respects in her touching article, Growing Pains. Meanwhile, Alexandra Morra discusses what it looks like to parlay schemas and guidelines adopted in the classroom into real-life clinical practice in From Classroom to Clinic. As part of our first ever QMRxMedLit collaboration, Andrew Lee reviews The Boy on the Beach a beautifully tragic real-life story about a group of Syrian refugees who tried to grow a new life by seeking asylum overseas (read it if you haven’t yet, and go to the next book club meeting)! On a lighter note, Sarenna Lalani offers up some green smoothie recipes to grow the healthiest body possible. We also added our hands into the mix with an interview-based series that asks medical students at different stages of their journey about their own growth, and a fashion column that shows you how to enhance your standard clinical skills wardrobe pieces. Finally, we are so excited to announce the launch of our new column, Dear QMR, wherein anonymous upper-year students answer questions submitted by members of the QMed community. We are so thankful for the silent contributions from all of you. We hope that this column is both fun, powerful, and emotional all-at-once! A special acknowledgment goes out to our hard-working managing editors, Grace Yin and Christine Moon, who have been pulling strings behind the scenes for the past couple of months, our content editors, Zoe Hu, Jessica Nguyen, and Sarenna Lalani for making sure we have all crossed our t’s and dotted our i’s (and also for making us all sound better!), and to our phenomenal artistry and layout team: Amanda Mills, Doan-Nghi Dam-Le, Jessica Nguyen and Andrew Lee who have completely revamped the look of the QMR for this issue! Whatever it is you seek out - there is something for you in this issue. We thank you for taking the time to support our creative endeavor, and to all of those who have contributed in their many ways. It takes a village, and we happen to reside in the best one out there. Nicole Krysa & Kimberley Yuen

1 Comment

By: Kimberley Yuen, Meds 2022 I interviewed a medical student from each year and asked them some questions about their medical school journey thus far. Brenna Han, 2023

What were you doing last year? I was working at a research lab at Western as a lab coordinator – it was my “year off” while I applied to med school. How do you think you’ve grown from last year to where you are now? Now I’m less afraid of making mistakes, not knowing an answer, and uncertainty. But last year I played it very safe because I was applying [for medical school], and for interviews I really couldn’t be as risky. But now because of this supportive environment I’m not scared to be first in clinical skills, needing help, asking people questions and things like that. I would say that’s the biggest difference – being more comfortable with taking risks and being uncertain of things. Is med school what you expected it to be? It’s better! QMed is definitely better than what I expected it to be. It’s more supportive. What do you think next year is going to be like? Hmm. Maybe I’ll care less about day to day classes and more about clerkship and looking towards long term goals (what kind of physician am I going to be, how can I be a better physician) vs. short term goals (eg. passing a final). Favourite thing so far this year? The people in my class. We have a really good class. We’re all extremely supportive of each other and we hype each other up so much. I think we have a very unique group of people but we all vibe really well together. We’re very receptive to learning from each other and not being afraid to make mistakes or ask each other for help. I think that’s honestly the best thing. 3 words to describe your med school journey so far: "unexpected, spirited, inspiring" Anything else you would like to share? There have been times (especially before a bellringer) when I’m having the worst imposter syndrome – I’m hoping by next year I’ll be able to work on that. I’m coming from a non-traditional science background and I think I’m one of the only ones in my class, making it a little isolating as I’ve never done anatomy before. I’m hoping next year I won’t be experiencing that and I’ll be more caught up. It’s not too bad, but lab is definitely difficult for me. Alessandro Ricci, 2022 What were you doing last year? How was it Last year I was in first year. Initially I found the excitement of being in med school to overshadow what I’m doing here and I found it really hard to shake that. I felt like I was still in undergrad and approached studying for classes the same way. Plus socially, I found a group of people that I related to the most and that initially was overwhelming because you spend your whole life trying to get to a place and sacrifice a lot to get there. There were gaps in my social life and support network and I found redirecting energy to filling those holes to be very very fulfilling. I feel like in first year I most strongly of the social aspect rather than academic. How do you think you've grown from last year to where you are now? Now I realize I’m going to be in the hospital next year and that changes the way I see things and study, in the sense that I study now thinking about what a patient would look like. I consolidate things based on how someone would present; studying like a clinician rather than an undergrad. I've also changed the way I look at failure as I now see failure as an essential part of this. I want to fail now so I don’t fail when I’m in the hospital, so I’m no longer as terrified of saying the wrong thing or making a mistake. What do you think next year is going to be like? Not scared at all. I'm actually very excited and I think that I’m excited not to be nervous anymore about clinical encounters because when I’m in clerkship I’ll be seeing a lot of patients. I usually get a little nervous in clin skills, but when I'm in the hospital I can learn the lifestyle. I love thinking about clinical problems and working through to the diagnosis. That combined with talking to patients, being constantly around people and treating people and clinical problems is the perfect combo (patient contact, critical thinking, learning). Is med school what you expected it to be? No not at all. In first year I was constantly surprised by everything and not knowing what the hell is going on in class or clin skills. I didn’t even know what med school would be like anyways. Now I understand it’s a very long training period (unlike a restaurant in one month you can be a server) but to be a doctor it’s 8 years and I look at it that way. 3 words to describe your med school journey so far? "Thoughtful, growth, challenging." Anything else you’d like to share? It’s important to find your people. And it’s important to take this stuff seriously. Craig Rodrigues, 2021 What were you doing last year and how was it? I liked second year a lot; the year was fast paced because every 6 weeks or so I immersed myself in a completely different organ system and specialty. When I was in first year, upper years told me that every specialty portrayed a different personality. I enjoyed looking for this during new blocks—I could definitely see it with some of the professors that showed up to teach us! Outside of school I held a council position that allowed me to travel to different cities, towns and meet medical students I’d otherwise never get the chance to meet. How have you grown from last year to where you are now? Back in undergrad and even in first year med I tended to compartmentalize things. I’d say my student life was basically school-work, social stuff, working-out (usually in that order). Having this mindset definitely worked for me in undergrad, but it usually meant when one element was more demanding—for example if a midterm was coming up—the other elements would suffer. Given that my student life is nowhere near done, especially with clerkship, residency and their associated assessments and workload, I thought it would serve me better to integrate my life a bit more. So in second year (and now while in clerkship) I try to be more flexible with my work-life balance. Sometimes it’s hard and I’m not the best at it… But I have noticed that I’ve started to balance things a bit better than I did in undergrad, and that’s a plus! What do you think next year is going to be like? Exciting and nerve-wracking. While electives are meant to focus on your learning experience and career exploration, in many ways they’re also try-outs for a program. I’ve heard some of my friends in fourth year mention phrases like “being constantly on” or “trying to see if you can fit”. Just like most educational/career steps in the past, with a good support system, knowledge base and adaptable mindset I feel like I’ll eventually settle into the expectations and culture of elective season and CARMS. For now, it’s all heavily anticipated! Is medical school what you expected it to be? I didn’t have much to do the summer before medical school, so I honestly thought about a lot! To answer the question, in many ways its a yes and no. Before o-week, a large portion of my anticipation surrounded my pre-clerkship years. I mainly focused and by extension created expectations about being in school, making new friends and learning how to learn medicine. I didn’t really think about the clerkship years and what it would be like being a new learner in the hospital. The growth and independence you gain when you’re placed in a new environment where you’re called to meet new teachers, learn vast amounts of knowledge on the fly and adapt to a new work environment all while being assessed is something that’s hard to justifiably explain to people that aren’t in medicine. It’s an unexpected ride and definitely something I’m enjoying so far. Favorite thing so far this year? The goodbye party some of our friends had after the White Coat ceremony, before everyone left for their regional sites! 3 words to describe your med school journey so far "Challenging, Doable, Formative" Anything else you’d like to share? If you have any q’s about clerkship hit me up! [email protected] Ramita Verma, 2020 What were you doing last year/how was it? I spent last year completing the bulk of clerkship. To say it was a rollercoaster would be an understatement. How do you think you've grown from last year to where you are now? I think last year may have been the steepest learning curve I have had to date. From a professional perspective, clerkship took me from being a classroom learner to bona fide doctor. All of a sudden when I read a patient stem on exams, I can think of someone who presented similarly. Things started to stick a bit more once I saw a patient and family who had the condition. Clerkship is also where I started to feel a bit less like a student and more like a working professional. Learning to meal prep, exercise, see friends and family, keep mentally well, while reading around cases and keeping up with professional responsibilities (and assignments) was a new balancing act. What do you think next year is going to be like? CaRMS! I think it's going to be busy and exciting. I'm applying to Family Medicine and could not be more excited to transition to residency. I am heartbroken to think about parting ways from my 2020s. Is med school what you expected it to be? I'm not sure what I expected when I got in since it was so long ago. The answer is probably not. I don't think I knew what medicine was when I got in or even until a year ago. Favourite thing so far this year? Electives - I took advantage of this time to learn about things that genuinely interest me that I didn't get to see during core rotations and this brought a lot of inspiration to what I see my professional career lining up to be. This and sharing 'clerkship stories' with my friends. 3 words to describe your med school journey so far? "Humbling. Community. Growth." Anything else you'd like to share? While going through medical school, I encourage you to think about the hidden curriculum and how this influences us. If you don't know what this means, talk to your peers (or upper years) about it. As my time at Queen's comes to an end, I think the most valuable trait of our school I've realized is our community and collegiality with classmates and other years. The way my peers and I have supported each other through the last few years makes me confident that they'll all be not only brilliant doctors but incredibly caring towards the patients and families they treat. Stay humble. Ask questions. Keep an open mind. Be kind. By: Valera Castanov, Adam Gabara, Minnie Fu, Meds 2022 Problem: Healthcare Growth Despite the Ongoing Healthcare Cuts Solution: QMedCare - a Student Run Clinic Student-Run Clinics Although Canadian healthcare is regarded as universal, major barriers to healthcare access exist for many Canadians. These barriers are a result of social, economical, and political disparities that consequently lead to increased hospital readmissions, higher rates of infectious and chronic disease, and ultimately, lower life expectancy (Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative, 2018). These challenges are exacerbated for those who do not have healthcare cards, guaranteed access to meals or shelters, or those who struggle to navigate the Canadian healthcare system. These include new immigrants, refugees, and those who struggle with home insecurity or substance use disorders. Recent cuts to healthcare such as the elimination of more than 800 full-time healthcare positions, cuts to 6 overdose prevention sites, and future plans to cut up to half a billion dollars in OHIP services, just to name a few, have dug deep into many medical services leading to ongoing shortages of staff, equipment, and space. Unfortunately, it is those that are most vulnerable with the least options that have the greatest to lose. As students and future Canadian healthcare leaders, we see an opportunity to use our time and energy to do something to help bridge this gap and address these unmet healthcare needs through the development of a student run clinic (SRC) here in Kingston. SRCs are a model of healthcare delivery that places students in a leadership position to organize and facilitate care under the supervision of licensed healthcare professionals. With at least one hundred operating in the USA, these free clinics hold an important role in providing primary care services to the poor and uninsured while offering medical students an educational opportunity to practice both their empathy and clinical skills. Starting in 1989 with a group of first year medical students at UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program who provided free blood draws and screenings at a local homeless drop-in center, this model arrived in Canada in 2000 when students from the University of British Columbia picked it up. Known as the Community Health Initiative by University Students (CHIUS), their clinic currently hosts an interdisciplinary student and resident-led team that partners with both the Vancouver Native Health Clinic and Three Bridge Clinic. With now more than 8 SRCs around the country, some of these clinics have expanded beyond medical services provided by medical students to become hotspots for interprofessional partnership. In Toronto, Ontario, The Interprofessional Medical and Allied Groups for Improving Neighbourhood Environment (IMAGINE) clinic has medical students interacting with pharmacy and nursing students to provide comprehensive care. Moreover, some of them have become community centers where patients can access social work, tax filing services, and in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, at the Student Wellness Initiative Toward Community Health (SWITCH), even pick up a hot meal for the day. Benefits of Student Run Clinics to the Community, Students and the System: With having an SRC, adding in interprofessional care that these vulnerable populations are unable to afford or access in the community, is both holistic and cost-effective. It provides patients the ability to engage in more holistic care of their own health, allowing them to take ownership instead of being subjugated to their circumstances. It allows them to not only have access to medications, but they will be able to obtain care for physical pain or conditions, social/mental/occupational issues, and potentially be able to achieve goals and have access to opportunities that they would not have been able to before. SRC’s have been shown to increase patient compliance, patient satisfaction, and have fewer return visits, which marry the two ideas of patient-centered care and ideal outcomes for patients (Charon, 2001; Gross et al., 1998; Cepeda, et al., 2008; Arntfield et al., 2013) Students will also benefit in that they will have the opportunity to interact with vulnerable populations almost exclusively in the SRC. They will better understand this population, be able to form connections with them, refine their skills taught in practical classes, and be able to carry forward this experience to their future practice with a more empathetic approach. Furthermore, current healthcare professionals lack a strong sense of what their other colleagues scope of practice is, which potentially can lead to confusion and lack of proper referrals (Curren et al., 2008). As such, students from the various fields will be able to witness and discuss cases with each other, fostering positive attitudes to colleagues from these fields that will hopefully carry forward into their careers. Coincidentally, student-run clinics also improve interest in primary care for medical students, where interdisciplinary care of patients is essentially required (Shabbir & Santos., 2015). An already clogged and overworked healthcare system benefits from the SRC model as well, as this holistic approach could keep patients out of emergency departments and avoid preventable hospital admissions (Thakkar et al., 2019, Kramer et al., 2015; Stuhlmiller and Tolchard, 2015; Arenas et al., 2017; Trumbo et al., 2018). Especially with having the multidisciplinary function, SRC’s will improve the quality of care and allow the clinic to tackle multiple issues at once. The SRC at theUniversity of New England in Australia,for example, has managed to save the health system an estimated $430,000 in their first year of operation (Stuhlmiller and Tolchard, 2015). Another SRC situated in Philadelphia managed to save an estimated $850,000 with an operating budget of only $50,000 (Arenas et. al., 2017). With strong evidence for the benefits of SRC’s, , the primary focus moving forward , is to assess the need and feasibility for this multidisciplinary approach in Kingston, Ontario., to ensure that patients indeed desire and will utilize these services for maximum benefit. Updates regarding the first Student Run Clinic in Kingston: Despite the proven benefits of opening a SRC to the community, students and the system, our team was faced with numerous challenges when pioneering the first SRC in Kingston. Firstly, finding the support of faculty and staff was challenging in the beginning phases of this initiative. As any novel idea, which is filled with uncertainty and more questions than answers, there was initial hesitation to support our proposal. However, throughout the past 6 months and many meetings, we were able to finally secure the support of the Office of Undergraduate Medical Education, and Inter-professional offices of Nursing, Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy at Queen’s University. Following a landmark meeting in October of 2019, the leadership of these programs agreed on the value of opening such a clinic in Kingston. However, it was also agreed that numerous challenges have to be overcome first before QMedCare - Student Run Clinic can be launched. One of the challenges outlined was defining the scope of responsibility of medical and allied health students. It was discussed at the meeting with faculty leaders that medical students would have the same scope of responsibility as during regular curricular observerships, with the duty of care ultimately on the supervising physician. This is the same structure of operations of other Canadian and American SRCs, and it makes sense. Pre-clerkship students lack the necessary knowledge and training and should be supervised at all times. The case is similar for interprofessional students, where a licensed allied health professional will have to supervise students and the duty of care will be ultimately on him/her. Another challenge discussed was establishing the continuity of the QMedCare SRC, not just at the intra-departmental level, but also at the inter-departmental. In medicine, QMedCare was recently approved by the Aesculapian Society as an official student interest group, which provides us with logistical support and financial backing of a larger organization necessary for the clinic to begin and continue its operations. Our team will soon begin the recruitment and training of next year’s executive council to further establish continuity. Recruiting students from the next cohort is essential, as they will be able to learn from the current council this year, and take over the leadership during the 2020/2021 school year. In terms of continuity in inter-professional departments, we were able to recruit two representatives from the schools of nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy and we will be discussing with them how they see establishing continuity of operations in their departments. Our team was very fortunate to find great support in our initiative from other Canadian SRCs. We had in-depth conversations with the IMAGINE clinic in Toronto and SWITCH clinic in Saskatchewan, who guided us throughout the start-up process, answered our questions and shared their experiences with us. Recently, we have joined the Canadian Student Run Clinic Association (SRCA), which governs and provides logistical support to SRCs. QMedCare will be sending its delegates to the SRCA Summit in Toronto on November 30th, 2019. Furthermore, we are very thankful to Dr. Meredith MacKenzie, Carol Lynch (NP), and the Street Health Centre (SHC, 115 Barack Street) who generously offered us training, supervision and clinic space. Without their ongoing support our initiative would not be possible. They have offered to host our clinic at SHC, under their supervision, every Tuesday from 5-9pm. We are so thankful for their generosity. As our team grew and became increasingly inter-professional, Valera - the founder and executive director of QMedCare, decided to rename the SRC to be more inclusive of our inter-professional colleagues. As this initiative was pioneered by Queen’s Medicine students, QMedCare was a great initial name of the initiative. However, as our team welcomed inter-professional members, it was an executive decision to rename the SRC for every team member to feel welcome and included. The new name of the clinic has not been decided yet, as we want to make it a collaborative decision with the input of all inter-professional members - which will likely occur at an upcoming meeting in November. Overall, our team was able to achieve great progress in a very short span of time and we are very proud of the work that we have done and continue to do. From securing faculty approval and support, supervision, clinic space and inter-professional collaboration, we came a long way from just “Valera’s dream”. Conclusion Regardless of the challenges, as future healthcare leaders we are obliged to do what is best for our community, patients, and colleagues, and therefore, we will work hard and do what is in our capacity to establish the first SRC in Kingston. Having talked to many other Canadian SRCs, every clinic had challenges when they first started. In many cases, it took years for their respective clinics to open. After all, Rome was not built in a day. We have heard from our colleagues that medical students at the Schulich School of Medicine at Western University have also recently brought the proposal of opening a SRC to help their community. This is very inspiring to see, as in the background of ongoing cuts to healthcare, medical students across Canada are striving to open pro-bono health-clinics to help the underserved and marginalized populations. Let’s contribute to healthcare growth together. Let's open the first student run clinic in Kingston! References:

Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative. “Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait – Executive Summary”. Public Health Agency of Canada. 2018 May 28. Charon R. “Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust”. Jama. 2001 Oct 17;286(15):1897-902. Gross D, Zyzanski SB, Cebul R, Stange K. (1998). “Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician”. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(2), 133 Cepeda M, Chapman R., Miranda N, Sanchez R., Rodriguez C, Restrepo A, ... Carr DB. “Emotional disclosure through patient narrative may improve pain and well-being: results of a randomized controlled trial in patients with cancer pain”. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2008; 35(6), 623-631. Arntfield SL, Slesar K, Dickson J, Charon R. “Narrative medicine as a means of training medical students toward residency competencies”. Patient education and counseling. 2013 Jun 30;91(3):280-6. Curran, V. R., Sharpe, D., Forristall, J., & Flynn, K. (2008). “Attitudes of health sciences students towards interprofessional teamwork and education”. Learning in Health and Social Care, 7(3), 146-156. Shabbir SH, Santos MT. “The role of prehealth student volunteers at a student-run free clinic in New York, United States”. Journal of educational evaluation for health professions. 2015;12. Thakkar A , Chandrashekar P, Wang W, Blanchfield BB. “Impact of a Student-Run Clinic on Emergency Department Utilization”. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):420-423. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.477798. Kramer, Nick, Jaden Harris, and Roger Zoorob. “The Impact of a Student-Run Free Clinic on Reducing Excess Emergency Department Visits”. Journal of Student-Run Clinics 1.1 (2015). Stuhlmiller, Cynthia M., and Barry Tolchard. “Developing a student-led health and wellbeing clinic in an underserved community: collaborative learning, health outcomes and cost savings.” BMC nursing 14.1 (2015): 32. Arenas, Daniel J, et al. "A Monte Carlo simulation approach for estimating the health and economic impact of interventions provided at a student-run clinic." PloS one 12.12 (2017): e0189718. Trumbo, Silas P., et al. "The Effect of a Student-Run Free Clinic on Hospital Utilization." Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 29.2 (2018): 701-710. By: Andrew Lee, Meds 2022 There is something bone-chilling about seeing the death of a child. We think about all of their potential, their missed opportunity for school, first school dance, first partner, first graduation, first child of their own. We are left with a void and too many what ifs. This was the story of Alan Kurdi, who forced the world to look deeply into the tragic death of a young boy.

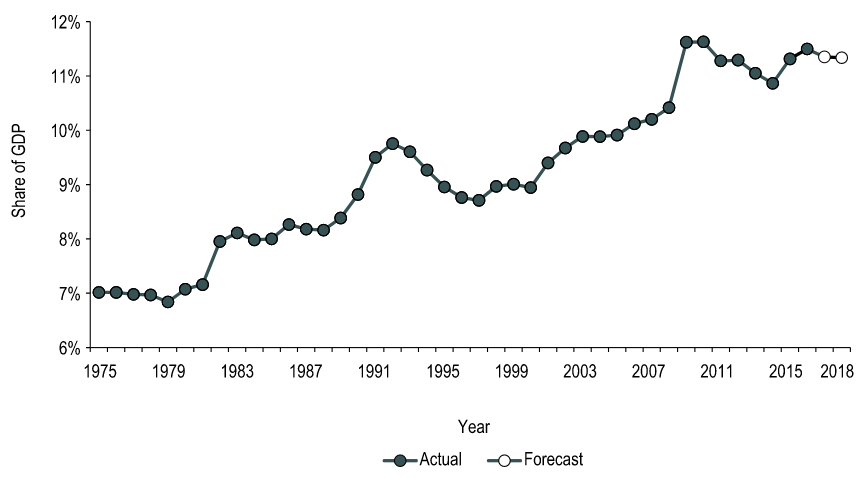

Fatima Kurdi left her modest home on the hilltops of Damascus, Syria in the summer of 1992. Little did she know, she was not merely fulfilling her dreams of exploring the world, but she was narrowly escaping a life of violence, torture, and political unrest. Syria has been the site of conflict since 2011, with many innocent people slain before their families. Life in Damascus could only be described by one word, family – a definition of family that expanded past blood relation. Warm and bright smiles, the beat of a drum every morning of Ramadan, and the smell of jasmine in the crisp summer air – these memories all make up Kurdi’s childhood. Kurdi traverses the trauma and hurt caused by the displacement of her family poignantly. She hints to her survivor’s guilt and the injustice her family faces. As her family becomes fractured, seeking safety in neighbouring countries, the book focuses on Alan Kurdi, the youngest son of her younger brother, Abdullah. She recounts Abdullah’s younger years – he was a charismatic child who elicited belly laughs from the entire room. A bit of a silly child, he would always find himself getting injured through his shenanigans. Their mother would say, “All these accidents, but he always survives. This boy is protected by mala’ekah,’ which means ‘protected by the angels’”. Abdullah’s characteristics and charms? were passed down to his little boy Alan. Alan, however, did not receive the same protection as his father did. As the Syrian civil war garnered international attention, some European countries began opening their doors. Thousands of people left Syria for Turkey. Unfortunately, the influx of refugees was not well-received and the capacity to hold them did not exist. It was difficult for refugees to find work and moreover, refugee camps were rampant with starvation and illness. These camps were not a feasible long-term solution. Countries such as Canada did not help. Fatima tried tirelessly to sponsor her family to Canada through refugee status, however, the government required a Turkish residence permit, which was not provided to citizens of non-EU countries. Their applications were at a standstill. Thus, refugees would tackle the fierce waves of the Kos river in hopes of seeking asylum in Greece. People would pay hundreds to thousands of Canadian dollars to smugglers offering flimsy plastic rafts in the face of tumultuous waves. As a result, many would drown on the journey to freedom and safety. Kurdi reminds us of our responsibility to humanity. She came to Canada as a hairdresser who knew very little English in hopes of starting a new life. She missed her home in Syria dearly and would visit her family often. As the conditions in Syria worsened, she longed to help her family, and she sent little of what she made to support their journeys out of the conflict zone. “The Boy on the Beach” reminds us that we yearn for the same things in life: family, love, security, and safety. Reading this book only reminded me how much hurt there is in this world and the frustrating bureaucracy that intentionally prevents refugees from seeking safety. Through her emotional and ingenious storytelling, Fatima Kurdi reminds us that we should not need to see a little boy dead on the beach to be angry, to be vocal, and to advocate for a better life for all. By: Victoria Lee-Kim, Meds 2022 QMed LEAD provided Queen’s medical students with the opportunity to hear from Don Drummond on the topic of healthcare economics and the growing national health expenditures. For those of you who are unfamiliar with him, he is a renowned Canadian economist who served in the federal Department of Finance, a professor at Queen’s School of Policy Studies, and was a Chief Economist at TD bank. His talk got me thinking—why isn’t healthcare economics more integrated into our medical education? We have diverse and strategic student minds that may eventually be able to combine their medical knowledge with policy, and may even be able to tackle the Canada’s growing health expenditure problem. Here are some of the striking statistics and insightful ideas he introduced, mixed with thoughts of my own: According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), in 2018, total health expenditure in Canada reached $253.5 billion (a growth of approximately 4.2%). That is 11. 3% of Canada’s gross domestic product. Also, approximately $6839 per person. To put that into context: using the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) statistics, Canada is above the OECD country average in terms of healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP and per-person healthcare spending. But why are we spending more than the average? Even accounting for the population spread over a massive amount of land, our split between public and private health care spending should theoretically equate to us spending less on healthcare. Our public-sector share of total health expenditure is 70% (30% private) which is below the average of 73%. For more context, the United States healthcare system is 82 % publicly-funded and 18% private. Canada is one of the top spenders, yet we constantly fall short in rankings of international health systems. If you ask me, something doesn’t quite seem to add up! Overall in Canada, the health-to-GDP ratio has trended upward in the last 40 years for reasons including general inflation, population growth, aging, novel drugs and infrastructure (Figure 1). Hospitals, drugs, and physician services make up the largest shares of health expenditures. In 2018, the annual growth forecast was 3.7%. We have to think of this trend while we practice medicine! The aging of the Baby Boomer generation will demand more of physicians, which means more hours per person or more people to compensate. Compensation currently accounts for more than 60% of hospital budgets, and thus is a huge cost driver. Moreover, old infrastructure must be replaced and increasingly expensive prescriptions are becoming the norm. The introduction of high-cost medicines can increase prescribed drug spending. These changes are predictable, but the issue is that our governments work in four year blocks, making it next to impossible to create systemic changes that will match the growth of healthcare expenditures. Figure 1. How health spending has changed in Canada over the last 40+ years; https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-spending/2018/national-health-expenditure-trends/how-has-health-spending-growth-changed-over-the-last-40-years You’re probably thinking “Ok… so what? What can we do?” Well, I’m obviously no expert and am aware that my opinion doesn’t hold a lot of weight, but I think awareness of these statistics is a good place to start! Awareness introduces an economic perspective into our future decisions as physicians. It can play a part in our willingness to provide preventive medicine, can help guide our choices of diagnostic tests , and help us decide which policies to advocate for. Who knows, maybe a QMed graduate will be at the forefront of systemic change that improves our healthcare system on a macro level! References

By: Sarenna Lalani, Meds 2023 Green G.I. Goodness What fuels the body feeds the soul amiright? Here’s a collection of green-inspired recipes to feed your soul this fall! Grow Green or Go Home Smoothie Bowl Vegan, gluten-free, soy-free A breakfast of champions that will make you feel ready to take on the day and feel great about sneaking in your veggies so early in the day! Prep time: 5 minutes Serving size: 1 serving Ingredients:

‘Oh She Grows’ Kale Lentil Soup (Adapted from ohsheglows.com) Vegan, gluten-free, nut-free, soy-free An effortless fall favourite great[1] for days that need a little something green! Full of fibre and packed with protein, this is a flavourful new recipe that is sure to make a recurring appearance each flu season! Prep time: 45 mins Serving size: 5 servings Ingredients:

Growin’ Strong One-Pan Meal Prep

Gluten-free, nut-free, soy-free A multi-meal solution so easy, you’ll be tempted to repeat it two weeks in a row! Healthy and efficient, this recipe is about to turn your meal prep Sunday into a meal prep FUNday. Prep time: 1 hour Servings: 3 servings Ingredients:

Directions:

So much of childhood, academics, finances, etc. are measured according to a common upward trajectory. Let’s frame this in a context relevant to all of us medical students. Particularly in the pre-clerkship years of medical school, we all learn the same material, at the same time, with the same exams and assessments of our progress at the end of the day. This can make it easy to have a sense of what you should know and where you stand. Come a certain point, however, most notably upon starting clerkship, this common path suddenly diverges in (a yellow wood…just kidding) multiple different directions. All these paths may lead to the same end-point eventually, but without 99 classmates moving alongside you anymore, how can you know that you’re moving in the right direction, at the right pace, or that you’ll actually end up in the right place? The fact of the matter is, it is really hard to be certain of these things. Wherever your path begins you will need to have a little trust that if you put in the miles, your route will eventually land you in the right spot – with all the same wonderful knowledge as your classmates.

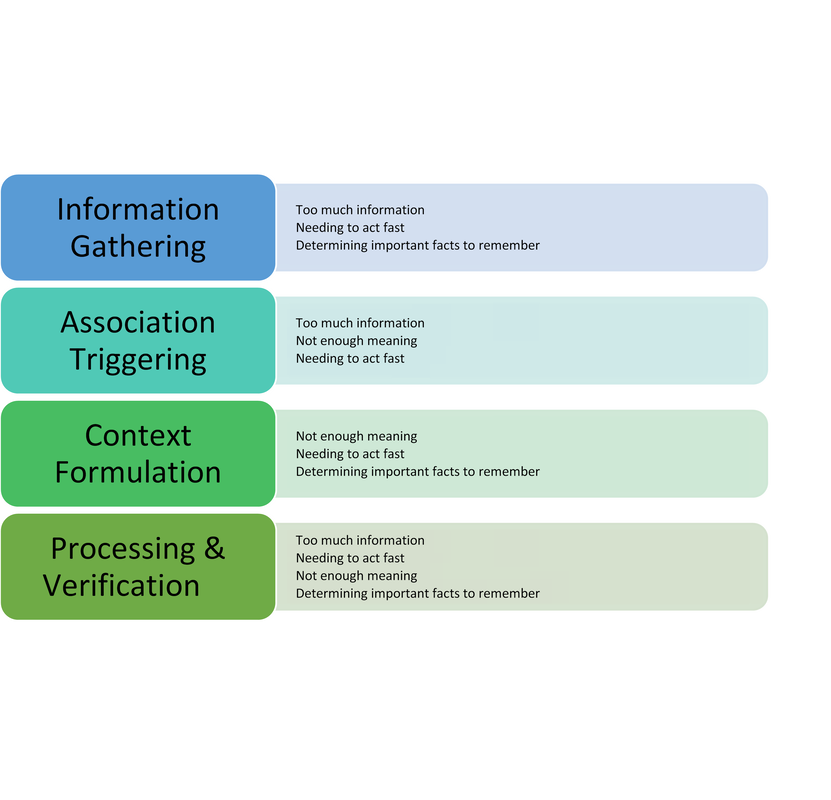

Underlying this transition from pre-clerkship to clerkship is a shift in growth from a common upward and linear climb, to an individual expansion in any number of directions. The growth trajectory remains upward – accumulating knowledge, skills and experiences. However, rate and order of learning will vary widely based on things like sequence of core rotations, different preceptors and residents, how quickly we strike a balance between work and life, and so many other factors both within and beyond our control. If we were to chart our progress through clerkship, some days might look like a failure to thrive, and others might really feel like a growth spurt. Just remember that even on days when the only question you get right is your name, you are growing. On days when you learn a new skill or get to show off something you have been practicing, you are growing. On days when you feel like you are underperforming, the fact that you have that awareness means you are growing. And, just like during puberty, it is normal to have some growing pains. We must take heart in knowing that whatever path we are on, we will eventually all get to where we need to go. Having said that, not all growth is painful. Growth also comes from hugs from a patient, suggesting the right diagnosis, or finding time to see friends, family or reading your favourite book. Welcome these moments warmly and continue to seek out the positives even on the toughest of days. Importantly, too, remember that not all pain means growth. Regardless of where we are at in our training, if we are feeling overwhelmed or run down, we must be kind to ourselves, to each other and try to connect with our support networks. There are people who care and who are there for you, whether these individuals are family, friends, partners, your class wellness representative, a counselor or others. Try to reach out and remember to keep an eye on those around us to offer a kind word. In summary, come a certain point in medicine, our development switches from common and clearly directed progress, to self-regulated and multi-dimensional expansion. We may not be able to measure our growth with pencil markings on adoorframe anymore, but the growth we now have the privilege of experiencing goes beyond what the eye can see. Medical school allows us to grow intellectually and emotionally, in skills and in character. Pre-clerkship is a great opportunity to practice what becomes necessary in clerkship and beyond – focusing on our own growth and learning independent of comparisons to others. Take heart in knowing that while we may not always enjoy the growing pains, it would be much more painful to always remain the same. Photo by Bret Kavanaugh on Unsplash. By: Alexandra Morra, Meds 2021 Patient X was your quintessential ‘man’s man’ – burly and statuesque, with a face caseated by a greying beard, reflecting years of wear and experience, and a brow furrowed with wisdom. He was a tradesman, evidenced by the calluses on his palms – his badges of honour from years dedicated to his craft. He sat in the chair adjacent to the computer, wringing his hands in his lap. ‘Anxiety’, I note to myself, ensuring to address such during our assessment. It became quite apparent, however, that his anxiety was rather warranted: Patient X was being treated for prostate cancer. A man who exudes strength and takes great pride in providing for his family, has had his raison d’être stripped from him, be it from androgen deprivation therapy or from long-term leave at work. According to Watts et al. (2015), one in four men will experience symptoms of anxiety after a diagnosis of prostate cancer and one in five will experience depressive symptoms. Not surprisingly, Patient X presented with insomnia and was frustrated at his hindered ability to engage in his daily routine. He was not one for being “idle”, he explained, “if you’re not doing something then you’re in the way.” A study done by Maguire et al. (2019) revealed that almost 20% of prostate cancer survivors experienced sleep dysregulation. Factors that contributed to sleep abnormalities that were parallel to Patient X [5] included urinary symptoms, anxiety, hormone treatment related symptoms, and a lower level of education (Maguire et al., 2019). Evidently, Patient X had more complexity to him than his original reason for visiting: a 3-month follow-up. Admittedly, it was my first day of clinic, and I was floundering. Having no inclination of where to begin, I quickly perused the patient’s chart, and began probing accordingly. Eventually, the patient disclosed a recent onset of dizziness. Glancing at the patient’s MAR revealed that he was on medications for blood pressure, and I immediately dove down that rabbit hole of questioning. Excitement slowly crept up inside me – had I successfully achieved my first diagnosis? Confident that his vitals would demonstrate orthostatic hypotension, I began his postural vitals, only to be left with a negative result. I was stumped and was so sure of my initial diagnosis that I could not think of other possibilities to add to my differential. Defeated and disappointed, I sulked back to my preceptor’s office waving the proverbial white flag, spewing what little oral report I could muster. He interrupted me mid-spiel. “Did you do a neuro exam? A Dix-Hallpike?” My cheeks burned with embarrassment as I disclosed my lack of diagnostic acumen, ashamed that I did not consider a neurological cause. Though this was a painful blow to my dignity, it triggered a curiosity into the cognitive biases we carry as practitioners, and their effects on our diagnostic capabilities. Buster Benson, an author with an interest in cognitive bias, whittled the myriad of existing biases into 4 essential categories: too much information, not enough meaning, needing to act fast, and determining important facts to remember (Benson, 2016). Arguably, maneuvering through the diagnostic process is often met with these obstacles, leading to misdiagnosis, adverse events, or even preventable death. In fact, 75% of errors in internal medicine alone are related to cognition at all steps of the diagnostic process (Graber et al., 2005, and Kassirer et al., 1989, as cited in O’Sullivan & Schofield, 2018). The studies by Graber et al. (2005) and Kassirer et al. (1989) identified the following steps in the diagnostic process: Information Gathering, Association Triggering, Context Formulation, Processing & Verification[6] . I initially postulated that errors would predominantly occur during context formulation. However, Singh et al. (2013) found that, contrary to my belief, 78% of cognitive errors occurred during the actual patient encounter! In our current healthcare climate, which is plagued with systemic issues that hinder optimal patient care, I can only imagine that physicians’ resort to employing cognitive biases as a means of being efficient, secondary to cognitive biases being a symptom of burnout[7] . Sherbino [Side bar: I worked with him in my previous job as a nurse!] et al. (2012) had observed that diagnostic accuracy was associated with decreased time spent in the diagnostic process, though I wonder if this more pertains to diagnosis formulation rather than information gathering. More applicable to me, however, was another study by AlQahtani et al. (2016), who demonstrated that novices’ ability [8] to correctly diagnose were hindered by having less time to do such (as cited in Norman et al., 2017). Figure 1 depicts steps of the diagnostic process and potential associated categories of bias. Reflecting on the brief literature review above, I likely utilized availability heuristic and anchoring[9] during my patient encounter. Availability bias is the use of “more recent and readily available solutions due to ease of recall” (O’Sullivan and Schofield, 2018), and anchoring refers to “relying too heavily on the first piece of information offered” (Pines & Strong, 2019). I was familiar and comfortable with the diagnosis and management of orthostatic hypotension, and pigeon-holed myself after noting the antihypertensive on Patient X’s MAR. Interestingly, Benson (2016) attributed these biases as a reaction to “too much information”, and as I (excessively) ruminated over this experience, it became quite apparent to me that I was simply overwhelmed. This past week has truly shed insight into the immense breadth of knowledge a family physician must carry in their cognitive repertoire. As a newly minted clinical clerk, I need to allow myself to accept that knowledge gaps will exist, and in fact, are an invaluable component of the learning process. Since my encounter with Patient X, I have begun to review upcoming patient appointments with a reinvigorated approach. I start by making note of the patient’s medical history, then review the literature on management of pertinent conditions from a primary care perspective. I have found American Family Physician to be quite valuable for such, as well as UpToDate. I may be in the infancy of my medical career, but I have already attained a plethora of knowledge in a mere seven days. References: ALQahtani, D. A., Rotgans, J. I., Mamede, S., ALAlwan, I., Magzoub, M. E. M., Altayeb, F. M., … Schmidt, H. G. (2016). Does Time Pressure Have a Negative Effect on Diagnostic Accuracy? Academic Medicine, 91(5), 710–716. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001098 Benson, B. (2016). Cognitive bias cheat sheet - Better Humans - Medium. Retrieved September 29, 2019, from https://medium.com/better-humans/cognitive-bias-cheat-sheet-55a472476b18 Dunn, J., & Chambers, S. K. (2019). ‘Feelings, and feelings, and feelings. Let me try thinking instead’: Screening for distress and referral to psychosocial care for men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13163 Maguire, R., Drummond, F. J., Hanly, P., Gavin, A., & Sharp, L. (2019). Problems sleeping with prostate cancer: exploring possible risk factors for sleep disturbance in a population-based sample of survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(9), 3365–3373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4633-z Norman, G. R., Monteiro, S. D., Sherbino, J., Ilgen, J. S., Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2017). The Causes of Errors in Clinical Reasoning. Academic Medicine, 92(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421 O’Sullivan, E., & Schofield, S. (2018). Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 48(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306 Pines, J. M., & Strong, A. (2019). Cognitive Biases in Emergency Physicians: A Pilot Study. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 57(2), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.03.048 Sherbino, J., Dore, K. L., Wood, T. J., Young, M. E., Gaissmaier, W., Kreuger, S., & Norman, G. R. (2012). The Relationship Between Response Time and Diagnostic Accuracy. Academic Medicine, 87(6), 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253acbd FIGURE 1: Potential Cognitive Biases at Each Step of the Diagnostic Process

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed