|

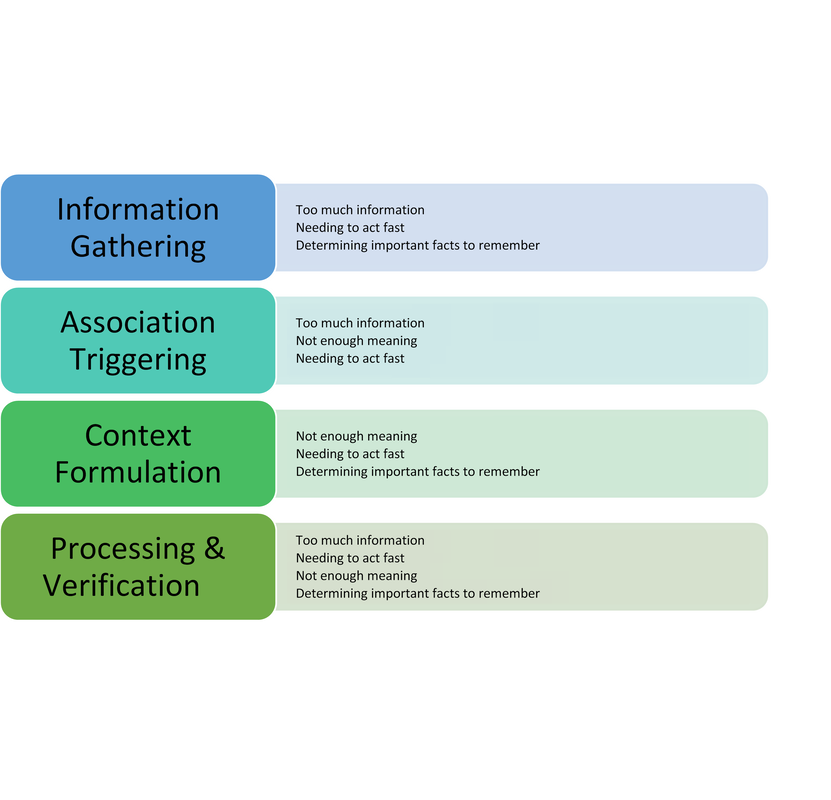

Photo by Bret Kavanaugh on Unsplash. By: Alexandra Morra, Meds 2021 Patient X was your quintessential ‘man’s man’ – burly and statuesque, with a face caseated by a greying beard, reflecting years of wear and experience, and a brow furrowed with wisdom. He was a tradesman, evidenced by the calluses on his palms – his badges of honour from years dedicated to his craft. He sat in the chair adjacent to the computer, wringing his hands in his lap. ‘Anxiety’, I note to myself, ensuring to address such during our assessment. It became quite apparent, however, that his anxiety was rather warranted: Patient X was being treated for prostate cancer. A man who exudes strength and takes great pride in providing for his family, has had his raison d’être stripped from him, be it from androgen deprivation therapy or from long-term leave at work. According to Watts et al. (2015), one in four men will experience symptoms of anxiety after a diagnosis of prostate cancer and one in five will experience depressive symptoms. Not surprisingly, Patient X presented with insomnia and was frustrated at his hindered ability to engage in his daily routine. He was not one for being “idle”, he explained, “if you’re not doing something then you’re in the way.” A study done by Maguire et al. (2019) revealed that almost 20% of prostate cancer survivors experienced sleep dysregulation. Factors that contributed to sleep abnormalities that were parallel to Patient X [5] included urinary symptoms, anxiety, hormone treatment related symptoms, and a lower level of education (Maguire et al., 2019). Evidently, Patient X had more complexity to him than his original reason for visiting: a 3-month follow-up. Admittedly, it was my first day of clinic, and I was floundering. Having no inclination of where to begin, I quickly perused the patient’s chart, and began probing accordingly. Eventually, the patient disclosed a recent onset of dizziness. Glancing at the patient’s MAR revealed that he was on medications for blood pressure, and I immediately dove down that rabbit hole of questioning. Excitement slowly crept up inside me – had I successfully achieved my first diagnosis? Confident that his vitals would demonstrate orthostatic hypotension, I began his postural vitals, only to be left with a negative result. I was stumped and was so sure of my initial diagnosis that I could not think of other possibilities to add to my differential. Defeated and disappointed, I sulked back to my preceptor’s office waving the proverbial white flag, spewing what little oral report I could muster. He interrupted me mid-spiel. “Did you do a neuro exam? A Dix-Hallpike?” My cheeks burned with embarrassment as I disclosed my lack of diagnostic acumen, ashamed that I did not consider a neurological cause. Though this was a painful blow to my dignity, it triggered a curiosity into the cognitive biases we carry as practitioners, and their effects on our diagnostic capabilities. Buster Benson, an author with an interest in cognitive bias, whittled the myriad of existing biases into 4 essential categories: too much information, not enough meaning, needing to act fast, and determining important facts to remember (Benson, 2016). Arguably, maneuvering through the diagnostic process is often met with these obstacles, leading to misdiagnosis, adverse events, or even preventable death. In fact, 75% of errors in internal medicine alone are related to cognition at all steps of the diagnostic process (Graber et al., 2005, and Kassirer et al., 1989, as cited in O’Sullivan & Schofield, 2018). The studies by Graber et al. (2005) and Kassirer et al. (1989) identified the following steps in the diagnostic process: Information Gathering, Association Triggering, Context Formulation, Processing & Verification[6] . I initially postulated that errors would predominantly occur during context formulation. However, Singh et al. (2013) found that, contrary to my belief, 78% of cognitive errors occurred during the actual patient encounter! In our current healthcare climate, which is plagued with systemic issues that hinder optimal patient care, I can only imagine that physicians’ resort to employing cognitive biases as a means of being efficient, secondary to cognitive biases being a symptom of burnout[7] . Sherbino [Side bar: I worked with him in my previous job as a nurse!] et al. (2012) had observed that diagnostic accuracy was associated with decreased time spent in the diagnostic process, though I wonder if this more pertains to diagnosis formulation rather than information gathering. More applicable to me, however, was another study by AlQahtani et al. (2016), who demonstrated that novices’ ability [8] to correctly diagnose were hindered by having less time to do such (as cited in Norman et al., 2017). Figure 1 depicts steps of the diagnostic process and potential associated categories of bias. Reflecting on the brief literature review above, I likely utilized availability heuristic and anchoring[9] during my patient encounter. Availability bias is the use of “more recent and readily available solutions due to ease of recall” (O’Sullivan and Schofield, 2018), and anchoring refers to “relying too heavily on the first piece of information offered” (Pines & Strong, 2019). I was familiar and comfortable with the diagnosis and management of orthostatic hypotension, and pigeon-holed myself after noting the antihypertensive on Patient X’s MAR. Interestingly, Benson (2016) attributed these biases as a reaction to “too much information”, and as I (excessively) ruminated over this experience, it became quite apparent to me that I was simply overwhelmed. This past week has truly shed insight into the immense breadth of knowledge a family physician must carry in their cognitive repertoire. As a newly minted clinical clerk, I need to allow myself to accept that knowledge gaps will exist, and in fact, are an invaluable component of the learning process. Since my encounter with Patient X, I have begun to review upcoming patient appointments with a reinvigorated approach. I start by making note of the patient’s medical history, then review the literature on management of pertinent conditions from a primary care perspective. I have found American Family Physician to be quite valuable for such, as well as UpToDate. I may be in the infancy of my medical career, but I have already attained a plethora of knowledge in a mere seven days. References: ALQahtani, D. A., Rotgans, J. I., Mamede, S., ALAlwan, I., Magzoub, M. E. M., Altayeb, F. M., … Schmidt, H. G. (2016). Does Time Pressure Have a Negative Effect on Diagnostic Accuracy? Academic Medicine, 91(5), 710–716. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001098 Benson, B. (2016). Cognitive bias cheat sheet - Better Humans - Medium. Retrieved September 29, 2019, from https://medium.com/better-humans/cognitive-bias-cheat-sheet-55a472476b18 Dunn, J., & Chambers, S. K. (2019). ‘Feelings, and feelings, and feelings. Let me try thinking instead’: Screening for distress and referral to psychosocial care for men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13163 Maguire, R., Drummond, F. J., Hanly, P., Gavin, A., & Sharp, L. (2019). Problems sleeping with prostate cancer: exploring possible risk factors for sleep disturbance in a population-based sample of survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(9), 3365–3373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4633-z Norman, G. R., Monteiro, S. D., Sherbino, J., Ilgen, J. S., Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2017). The Causes of Errors in Clinical Reasoning. Academic Medicine, 92(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421 O’Sullivan, E., & Schofield, S. (2018). Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 48(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306 Pines, J. M., & Strong, A. (2019). Cognitive Biases in Emergency Physicians: A Pilot Study. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 57(2), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.03.048 Sherbino, J., Dore, K. L., Wood, T. J., Young, M. E., Gaissmaier, W., Kreuger, S., & Norman, G. R. (2012). The Relationship Between Response Time and Diagnostic Accuracy. Academic Medicine, 87(6), 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253acbd FIGURE 1: Potential Cognitive Biases at Each Step of the Diagnostic Process

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed