|

Dear lovely readers,

We are pleased to present to you our third (and final!) issue as Editors-in-Chief of the QMR. It has been such a privilege to have been a part of the longstanding QMR community, and we have loved every minute of it. Although the QMR tradition has been a constant for many years in QMed, we have found ourselves releasing our final issue in truly unprecedented times. COVID-19 has had widespread impacts on Queen’s students, as well as the medical community. Students have been displaced from their usual learning environments as their preceptors bravely face the virus head on. As such, we felt that we could not launch this issue without devoting a significant portion of it to this once-in-a-lifetime event. We invited contributors to submit pieces under either our initial theme of Conversation in Medicine or the theme of COVID-19. The outpouring of responses that we received were wide-ranging, inspiring, and thought-provoking. We hope that they serve as a reprieve from the stress that accompanies these difficult times. As always, an emphatic thank you goes out to our devoted Managing Editors, Grace Yin and Christine Moon. They have been working diligently behind-the-scenes for the past year to ensure that all trains run on time. An additional acknowledgement goes out to our Editorial team; Mike Christie, Zoe Hu, Sarenna Lalani, Grace Yin, and Jessica Nguyen, who have meticulously ironed out our wrinkles to ensure that all our articles read in the best way possible. Finally, our design team, who have collectively revolutionized the aesthetic of the QMR over this past year; Amanda Mills, Andrew Lee, Doan-Nghi Dam-Le, and Jessica Nguyen. You have each dedicated so much time and effort, and added your personal touches to make the QMR look amazing. We couldn't have done it without you! A special shoutout also goes out Kiera Liblik for coming onboard this issue and providing us with some beautiful graphics. Thank you again for supporting us through your readership and enthusiasm over the past year. From the bottom of our hearts, we are so grateful. We wish you all health and safety during these times. As a collective QMed family, we will get through this. Your Editors-in-Chief, Nicole & Kim

0 Comments

Iku Nwosu, Meds '22

We start off the year full speed ahead, spirits ablaze. Whether it is orientation week, meeting 100+ new faces as first year students and group leaders, or even just coming straight into class (the infamous, well-loved Cardio-Resp block), suddenly you cannot catch a break. You may have a plan at the start of the term; there is always a plan. You want to be disciplined, eat healthy food, work out often, have some nights out with your friends, and even keep up with the DILs. You also want to be involved “just enough” to keep your CV on edge. Two weeks into second year for me, I was already starting to burn out. I am the first to admit I probably do too many things. And no, this is not a humble flex or subtle brag. Being busy is not cute. Overworking yourself is far from a “vibe” when you are actually living in it. It is easy to judge someone who suddenly chooses to drop a commitment or group, but when I see it happen, I have started trying to understand. Dedication is an important skill to develop but not at the expense of your wellbeing. The whirlwind of everything we “balance” can start to make you feel suffocated. Now, you might already see where I am going with how this relates to COVID19. In the last couple of weeks, all the commitments we have had look completely different or are off our plates altogether. The kind of free time I have now is honestly baffling. If you are someone who makes to-do lists like me, you have probably laughed to yourself about how short it can be these days. It is in some ways relieving if I am being completely honest. The Spring Formal I no longer have to plan and promote, the interest group meetings I do not have to squeeze into my schedule, the lunch talks I can attend comfortably from my bedroom, amongst everything else academic that has shifted. I do not want to downplay the severity of this pandemic or disregard the immense privilege I and many others have. We are very fortunate to be able to go through this with some semblance of normal or feeling of safety. However, if there is one simple notion that I can take away from this time (and there is no pressure to have to “take away” anything during a pandemic), it is this: I was spread astonishingly too thin. Perhaps when we re-enter life as we knew it, as joyous as this prospective occasion will be, I will try to do so not as full speed ahead. By Michael Scaffidi, Meds '22

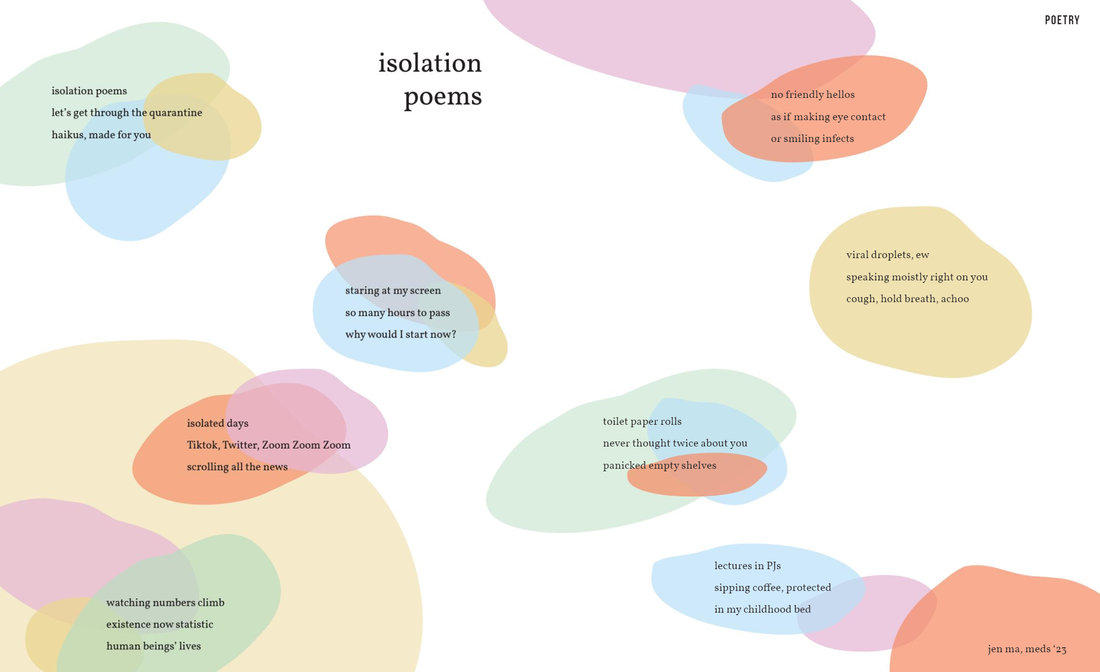

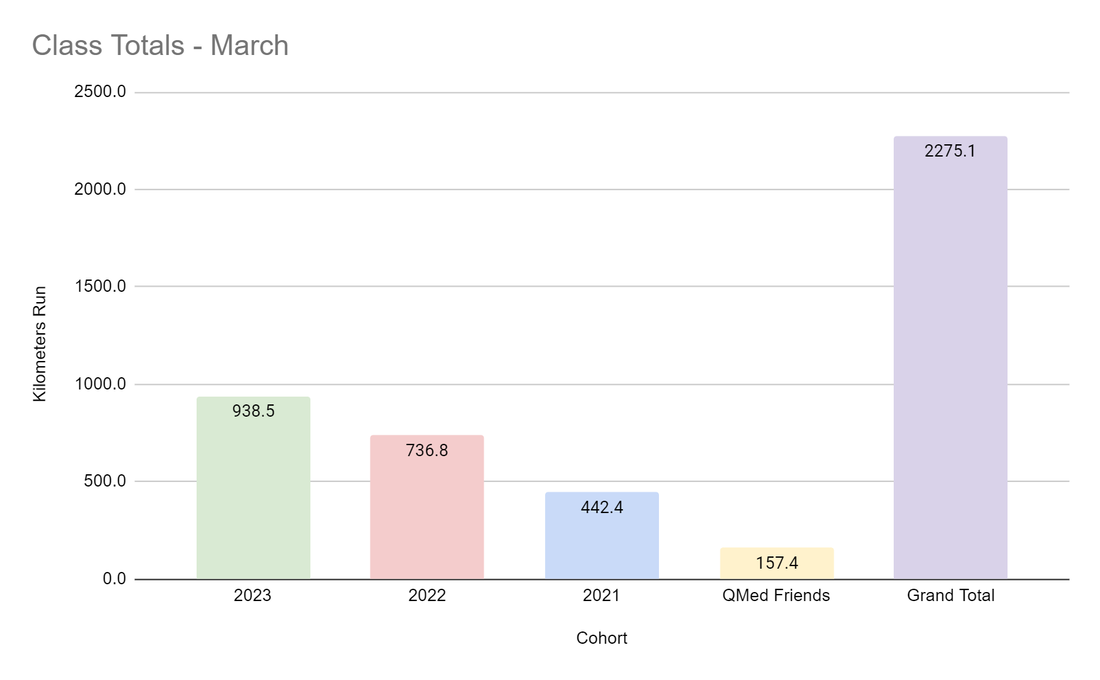

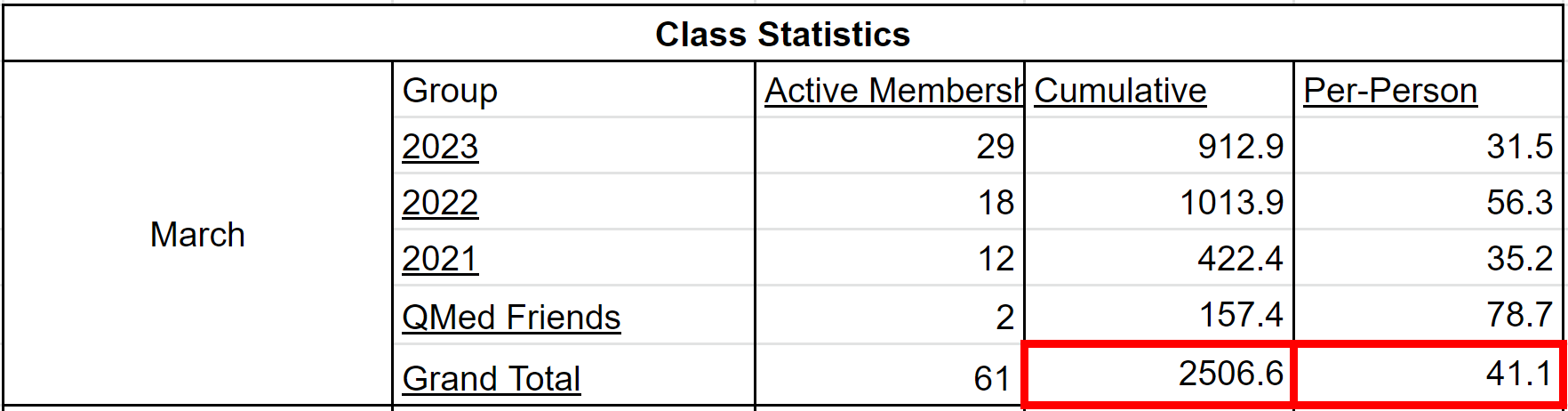

As medical students, one of the first skill sets that we are taught in the curriculum is communication. We are instructed on how best to interview patients using DISCLO TRAAAP A SOUL, PQSRT, or the Sacred Seven. We’re also taught to listen and to enter into a dialogue with patients. Sir William Osler said it best: “Listen to the patient. He [or she] is telling you the diagnosis”. While communication with patients is important, it is not the only important type of communication in medicine. We also need to be cognizant of how we communicate with each other. There is a growing evidence base – which, and this is a shameless plug, my lab has happily contributed to, showing that “non-technical skills” have an appreciable impact on patient care. One non-technical skill is that of interpersonal communication. Intuitively, this relationship makes sense, as better communication amongst colleagues leads to better collaboration and delivery of care. After all, medicine is a team effort. And yet, how many of us many of us strive to use “effective communication” in our day-to-day interactions with one another? I know that I certainly struggle with it. By “effective communication”, I’m referring to the act of expressing oneself genuinely with one another without pretense or façade. This concept seems like common sense – after all, we all got to medical school by knowing how to behave and act in a professional manner. Nevertheless, it can be easy to fall into the trap of mincing our words or not speaking directly to our peers. I’ll give an example from my own experience. Before medical school, I used to work in a lab. One of the constant sources of unease was discussions surrounding authorship. In particular, there was a project in which the medical student with whom I was doing the study — let’s call him Josh, approached me about authorship surrounding the paper. Josh was rather direct about it, asking me for first authorship. Josh had certainly done a great deal of work — he collected data from a number of participants and had spent hours organizing the data. At the same time, I had also done a considerable amount of work with data collection, in addition to designing the study, writing the protocol, and submitting the ethics approval. I remember being initially taken aback by Josh’s candor. In fact, it would not be a stretch to say I was more than a little irritated with his approach. He had only been involved in the lab for two months and here he was asking for first authorship. My initial instinct was to defer the conversation indefinitely. We both had compelling reasons to vie for first authorship, but I felt that I had done the lion’s share of the work, including both the leg work of data collection and the intellectual development. So I asked Josh for time to think about it. And in that time, I wrote out a list of arguments for both sides. In the end, I decided my work had merited first authorship, but I also realized that Josh had put in a huge effort and had significantly helped advance the project. In the end, I told him directly that I thought that I should be first author, while proposing that we share authorship as joint co-first authors. Josh agreed and we completed the study together smoothly. Looking back, however, I am thankful for Josh’s direct approach. Although I was not used to his candor, I learned that it was for the best — not only did we finish the study without a hiccup, but we became fast friends. In fact, Josh and I are close friends and colleagues to this day. Effective communication, though sometimes initially uncomfortable initially, can serve as a powerful forge for strong relationships. After all, diamonds are made under pressure! What did I learn from this interaction? First and foremost, it’s important to be direct when expressing your needs and concerns. It would have been easy for Josh to sweep the issue under the rug and not ask in the first place. Yet, he recognized that his argument had merit and was worth bringing up. Moreover, we had our conversation in person, which minimized any possibility of misinterpretation. While email and online messaging present expedient ways to communicate, they can often unnecessarily introduce ambiguity into a conversation. Alternatively, talking with someone in person allows fidelity of discussion, as we can physically see how the other reacts to what we say. Second, Josh approached the situation in a way that was firm while remaining respectful. Sometimes, we can fall prey to the idea that we’ll only be taken seriously if we are aggressive. While there are times when we need to take a hard-line stance, it is often the case that respectful assertiveness will go a long way in ensuring receptivity. Josh and I were extremely polite through our discussions, which ensured that we both gave the other space to hear and listen to each other. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is a need for dialogue. Yes, we each have our own wants and needs. “Of course, everyone does, Michael”, you say in your head, “Are you saying that I don’t think of others?”. No, not at all, dear reader. What I am saying, however, is that it can be easy to gloss over what would best serve others for what we would like for ourselves, especially if we’re angry, tired, or stressed. And yet, putting in even a little effort to empathize with the other person can make a difficult interaction into a bearable one. In the example above, it didn’t come easy but I forced myself to see Josh’s perspective by literally writing it out. Talking with colleagues or friends for their opinion is another approach. As I come to the end of this article, I want to end with a reflection on my ongoing journey with effective communication. As I mentioned earlier, I have done work with my lab in the area of effective communication and medicine. Although useful, this work led primarily to theoretical knowledge. I provided the example of Josh to illustrate a milestone in my practical understanding of effective communication. This understanding has only grown from having experienced effective communication among the interactions with many of my fellow classmates and friends in QMed. I am fortunate to be surrounded by many effective communicators. There were many times where misunderstandings could have easily been blown out of proportion. Yet, we were able to resolve the issues amicably because we were direct, respectful, and empathetic with one another. In other words, we used effective communication. As we move throughout our training, especially in these strange, uncertain times of the COVID-19 era and beyond, I know that we’ll need to rely on effective communication more than ever. It’s easy for tensions to run high on the wards, when life is hectic and fast-paced. However, I am confident that effective communication will help us see it through. Sean Leung, Meds '22 Unwilling Beginnings Let’s see… how did this all start? It was March 2018 – about two years from me writing this right now. I didn’t even like running. Cardio sucked. I never did it. All I needed were protein shakes and the iron temple. But then one day my best friend Darren messaged me asking me if I wanted to run a 10K. “Bro, I don’t do cardio LOL”, I said. He said “Come on, man”, and told me I’d be getting a Lululemon shirt – and the cost of registration was less than the value of the shirt itself. Well, I mean… sounded like a pretty good deal to me! So, I signed up. The next day, I started training with my housemate, Max. That still sucked. I couldn’t even run 500 meters without slowing, stopping, gasping for air. Honestly, if it weren’t for him dragging me out for workouts, I probably would have quit. I’m a social exerciser and I easily lose motivation when training alone. So, trailing behind Max on every run, I endured it. I won’t lie – I still hated running. The air was cold and harsh, I was tired, and it was hard to breathe; but I began to find solace in the warm company, the refreshing nature, and the burst of endorphins waiting for me at every finish line. I ran the race, and I beat my target time by 4 minutes. It was a thrilling experience to run in the middle of the highways of downtown Toronto, surrounded by several thousands of people, and breaking personal records in a legitimate race. It was equally awesome getting my shirt. Birth of the QMed Run Squad (QRS) I thought that was it. Another bucket list item ticked off. Great start to the summer. Back to the no cardio life. Little did I know, running would soon become an integral component to my life, and a gateway to a community that would grow to inspire and motivate me every day. Fast forward to the end of August 2018. I’d just moved in to my new house in Kingston, ready to start up my new life at QMed. I didn’t really know my housemates at the time, so I shot my shot and asked if anyone wanted to run with me. Kim said she was down, and all of a sudden, I was much less anxious about making new friends. The familiar feelings of companionship flooded my brain, and I realized that day: I actually liked running. Come December, a classmate and former varsity track star named Clare McGrath asked if she could run with me and Kim. I said “Of course!”, not knowing that this woman would, in the following months, completely destroy and rebuild me as an athlete. As our little squadron continued our workouts to keep cozy through the frigid grips of the winter, March crept back around – a year from when I first began running. I thought “maybe it’s time to do a race again”. We started up a group chat called “Run Squad” on Facebook Messenger, excited whenever someone new eagerly joined in. With blossoming membership, Clare and I started to design a training plan for the Sporting Life 10K and Lululemon 10K. Our philosophy was to create a training group that was fun and accessible to people of all levels. So, we planned workouts with defined training sites so that everyone could stick together; and we implemented a “satellite” rule for longer runs, where more seasoned athletes could orbit around more novice runners. We got started, and quickly ramped up the mileage. The training was brutal, but exhilarating. New friends joined here and there. I even managed to convince this cute girl named Jessica Nguyen to run with me. And all together, the QRS got better, faster, and stronger. Then came September anew, and a whole new class came to QMed. A fresh new cohort of people to lure into my kilometer crushing frenzy. Our membership shot up to 33. We had people from 2021-2023 join in. It was an amazing community, everyone ready to get sweaty and tired together. It spurred my inner social athlete on, having a group to rely on. Catching sunrises and boosting our VO2max became my escape. I loved the sense of purpose, rising before the sun, going out to meet my fellow crusaders, ready to combat any terrain or weather. QRS truly became part of my enormous pride in QMed. I was ecstatic. It was February 2020, I created a new 10K training plan, and had just started convincing people to sign up for races. Then, suddenly, we were met by our greatest adversary: the COVID-19 Pandemic. The COVID-19 Era Everyone had to go home. To fight the virus, we couldn’t see each other. It was a complete 180. We couldn’t run together anymore. All our plans to run races and train together – gone. I tried going on runs by myself. It felt like crap. My motivation was shot. Where before I could run any distance with QRS by my side, I could hardly finish 5km by myself. It felt like I regressed to that first run in 2018. I was crushed…but I wouldn’t be defeated. And I wanted to keep the group alive. We started to post updates of our workouts in the group chat. A quick selfie and Strava post here and there. It soon started to feel like I was running with everyone again. I guess that’s the great thing about running: it’s portable. It didn’t matter that we were all pushed to our own little corners of the Earth. We were as connected as ever – and the loneliness of social distancing began to fade. Eventually, we had the idea of seeing how many kilometers we could run cumulatively. And thus, the Run Bank was born. It started initially as a group effort to rack up distance. But leave it to Queen’s medical students to turn it into a fierce (but fun!) competition. Our membership almost immediately doubled to 62, with athletes diligently updating their spreadsheets with every workout conquered. People who had never run before started to join. Others set new goals, drew up plans, inspired their families, and broke through past limits. I can’t express how bizarre of an experience it is to look teary-eyed at a spreadsheet, bubbling in pride and joy. In just 2 weeks, the Run Bank demolished 2506.6 kilometers. The average runner contributed 40.4km. I’d created a monster, and I’m determined to keep feeding it. Harnessing our invincible inertia, we decided to take it to the next level. Set near the end of April, QRS is hosting a virtual 5K and 10K race. I can’t wait to see what our athletes can accomplish.

This pandemic has sunk its teeth into the very way we as humans live our lives. Each and every one of us is making sacrifices in our own way, whether it be by serving on the front lines, volunteering to help those in our communities, or simply staying home to curb the virus. It’s hard, and it’s taxing. Amidst all this, we can’t forget to take care of ourselves and each other. Maybe we all run for different reasons. Maybe we’re all at different fitness levels. Maybe we’re all in different places. But hopefully, by running, we can escape the weight of the dread. We can welcome the surge of endorphins. We can embrace the crisp fresh air of the outdoors. We can bathe in the warmth of each others’ company. All together. All apart. Written and illustrated by Christine Moon, Meds '23 Since December 2019, the global viral pandemic of SARS-CoV2, has been assaulting the health of people all over the world. Here at home: in our nation, in our province, and in our own school, we rely on leaders to mobilize resources, communicate important scientific information, and protect the population. Here are the profiles of four women who are doing just that. Dr. Theresa Tam, BMBS Role: Chief Public Health Officer of Canada Training: BMBS (University of Nottingham), Residency in Pediatrics (University of Alberta), Fellowship in Pediatrics Infectious Diseases (University of British Columbia) As head of the Public Health Agency of Canada, Dr. Tam is responsible for leading her organization and indeed the nation, in times of crisis. In the past, she has been a leader during the SARS, H1N1, and Ebola outbreaks. Now, her daily updates, informed by clinical science and epidemiology, help inform both the public and health professionals across the country. Sharon Yeung Role: Co-chair of the Ontario Medical Students’ Association (OMSA) Training: MD-MSc (Epidemiology, Queen’s University) As co-chair of the Ontario Medical Students’ Association, Sharon supports medical students province-wide in their efforts to aid with the COVID-19 pandemic. She works with the Ministry of Health to find opportunities for students to be involved in contact tracing and public education. She has developed a central online hub through the OMSA for volunteer opportunities and medical student initiatives across Ontario, and has been instrumental in connecting medical student initiatives (for example, initiatives to gather donations of PPE), encouraging collaboration and idea-sharing. Sharon is not only a leader at Queen’s but also for medical students province-wide. Dr. Michelle Gibson, MEd, MD Role: Assistant Dean, Curriculum for UGME at Queen’s Training: MD (Memorial University of Newfoundland), Residency in Family Medicine & Care of the Elderly (Queen’s University), MEd (Queen’s University) You know her as a beloved professor of geriatrics, but in recent weeks she has been the voice of support for students as we navigate a move to online learning. Her cheery update emails (and reassurances on Zoom), filled with concern for our well-being, make these scary and unpredictable times a little less so. We appreciate her efforts behind the scenes to make our online transition as smooth as possible and we all can feel a little more comfortable, knowing that she is doing everything in her power to support us. Dr. Eileen de Villa

Role: Medical Officer of Health for City of Toronto Training: MD (University of Toronto), Residency in Public Health and Preventative Medicine (University of Toronto), MHS – Health Promotion (University of Toronto), MBA (York University) As the leader of Toronto Public Health in the province’s capital, Dr. de Villa has been a leader in Ontario’s public health since her appointment in 2017. Her harm-reduction approach for personal use drugs, as well as her outspoken advocacy against the Ford government’s cuts to the health budget, has made her a household name in the last three years. Her continuing voice of reason (sometimes in the face of political crosswinds) makes her a great advocate for the health of all during this uncertain time. Emily Wilkerson, QMed 2021

It’s very hard to ask a question when you’re afraid of the answer. I can remember sitting there like it was yesterday. It wasn’t a private room, but my grandfather was the only occupant. My grandmother, mother, and I sat in a row on a bench against the wall, facing the end of the bed. The doctor sat in a chair that she brought in with her, and the nurse stood next to her keeping one eye on my grandfather, and the other on my grandmother. It wasn’t the first family meeting we had, and it wouldn’t be the last. It was, however, the first meeting in this new room, with this new doctor, who was now my grandfather’s palliative care physician. My grandfather had just been moved to palliative care after a series of unfortunate events leading to a decline in his health. He had poor shortness of breath and pain control, and we were hoping that making him more comfortable would give us more time. Now that things were a bit calmer, we had to ask the impossible question – how long do we have? During this conversation, the question never came out quite as bluntly as that. We danced around it, as if to avoid getting burnt by a campfire. Slowly chipping away at our concerns, we finally mustered the courage to say, “Are we being dramatic by having our family fly in to see him by then end of the week?” Taking a deep breath, the physician responded while gently shaking her head, “No. You’re not being dramatic. Everyone who would like to come, should come now.” It took a significant amount of courage for us to ask this question. We wanted to have all the answers and to know what was coming so we could be prepared. At the same time, we wanted to be blissfully in denial. It wasn’t our intention to step into a world where our timeline was cut down from two months to two weeks, but so we did. We had to be brave so that we could make the most of the time we had left and so we could stop fighting against the clock, and start working with it. Those two weeks were the slowest two weeks of my life. The days blended together into one. It was as if time stood still. And finally when it was all over, it went by too fast. Even now, some days it feels like it never happened. In our clinical skills practice in medical school, we have sessions to prepare ourselves for difficult conversations in medicine. Using the SPIKES framework, published in The Oncologist in 2000 by Baile et. al., medical students are placed in simulation environments to practice delivering “bad news.” These simulations are designed to help the medical learner set up a space with a patient and their family in order to communicate key pieces of information, while remaining mindful and empathetic towards the patient.1 These simulations are surprisingly difficult in the beginning. With my first scenario, I felt clumsy, trying to lessen the blow by avoiding harsh words. However, this only confuses the truth. During feedback from the patient actor, they explained that what they really needed was for me to just be honest. While these simulations are extremely valuable, nothing quite prepares you for the day when you must actually deliver bad news, no matter how small, to a real person, with real consequences. Then perhaps your training serves you well, and you get through the first conversation without much difficulty. Soon you realize that in reality it’s not just a single conversation. Rather, it’s a series of difficult conversations, difficult questions, and difficult answers. I always imagined that to the outside world, physicians, being used to deal with these hard conversations over time with their patients, would somehow be better at receiving it. One would think that since they’ve been on one side of the conversation, they may know all the right questions to ask. They might be eased by their intricate medical knowledge and by the understanding of the progression of chronic disease. They can see it coming, so it doesn’t come as quite a shock. In my experience, this couldn’t be farther from the truth. When it came to having this conversation, it was impossibly hard. I had been in this situation before on the other side of the table, but instead I felt like I was in the passenger seat of a speeding car and had no control over where we were going. It is always interesting to reflect back on the reversal of the role of patient and physician – and when you think about it, it is a privilege. How can we sit on the physician side of the table and truly understand what goes through the patient or their family’s minds when they are receiving bad news? This is not to say that we as medical professionals cannot be empathetic, conscientious, and mindful communicators. It might just mean that until you experience it yourself, you can’t truly understand the patient’s experience. In the future, I hope that I will never take for granted having a difficult conversation with a patient. These conversations are moments that last in the minds of our patients and their loved ones forever. They are implanted like art work framed on a wall. These moments are opportunities for connection, for empathy, and for offering peace of mind. I am grateful for the palliative care physician who chose to be honest with us. There are no certainties in the prediction of when death will come. You can only be patient and be quiet. To a mere medical student, this might feel like forever in the moment, but for the patient, there is never enough time. References 1. Baile, W.F., Buckman, R., Lenzi, R., Glober, G., Beale, E.A. and Kudelka, A.P. (2000), SPIKES—A Six‐Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. The Oncologist, 5: 302-311. Mike Christie, Meds '21 After a few months of clinical, I’ve come to the realization that effective conversation in medicine is its own art form. The physician has the role of immediately building trust and rapport with complete strangers, albeit while conversing with a wide diversity of people who present in a swirling myriad of contexts. Situations can change rapidly from patient to patient. Sometimes the circumstance surrounding a conversation is turbulent, emergent, panicked, or tragic. Other times, it’s jubilant, relieving, or routine. Combining the variety of situational dynamics with various personalities, at times I’ve found it both equally intriguing and challenging to communicate with the patient, or person, sitting across from me. From watching experienced physicians do their thing, it’s clear that effective medical conversation takes tremendous focus, tact, and humility. All of these docs admit that mastering the Art of Medical Conversation takes a career to learn. However, through their own examples, they’ve passed along some insights that have built a solid foundation off of which I’ve been able to learn. I think the basic - yet overwhelmingly human - essence of these principles make them something that every medical student should know.

First off, you can’t have a conversation with a patient if they can’t hear you, you can’t hear them, or even worse – both! It’s okay to turn down the blaring TV in a patient’s room or close the door if there’s a commotion out in the hallway. You may have to raise your voice to what feels like an incredibly loud volume – we’re talking rock concert levels – when conversing with a hearing-impaired patient. Sitting down when at the bedside can help with hearing, and it erases perceived power dynamics at the same time. I have even seen a patient put in the earpiece of their doctor’s stethoscope while the clinician spoke through the bell. (Don’t worry, there were disinfectant wipes involved before and after). Regardless, setting the stage for conversation with something as simple as making sure you can hear one another is a critical, but often overlooked, first step. “Patients don’t read the textbooks on how their disease presents!” It’s a line we’ve all heard at one point or another in our training, and it’s true. Patients typically don’t describe symptomology or progression of illness in a clear-cut timeline that perfectly matches classic clinical presentations. Obviously, part of the Art of Medical Conversation is carefully reconstructing the sequence of events in a medical history – that’s what we’re there for. The reality is, though, that it can be quite puzzling. Add in the pressure of limited time and it can quickly become overwhelming. It’s key to remember that it’s okay to pause, backtrack, and ask for clarification on timing of symptoms or events. Initially I was worried that patients would (incorrectly) view this as a result of inattention, however over time it became clear that they instead appreciated that I was being thorough. It’s more efficient to invest a few moments up front to avoid having to go back again at a later time. On a pertinent practical note, when patients struggle with remembering timelines or frequencies, using generalizations of timelines “days, weeks, months, or years” has proven highly effective at helping quantify a timeline. Part of collecting information from patients involves asking them a certain list of questions to ascertain critical details about their condition or clinical presentation. The challenge with this when first starting out is that it can be exceptionally difficult to focus on a patient’s answer to a question while at the same time considering what to ask them next. One helpful strategy for managing this is simply taking notes as you go along to more easily follow the conversation and have a quick summary available for review if you feel lost. Another key point is knowing that you are, in fact, allowed to pause and think for a few seconds! The interaction doesn’t have to be a rapid fire of back and forth. Pauses can feel tremendously awkward, however patients understand if you need a moment to consider which routes to explore with your next question. If there was one thing that at first put me a tad off-kilter, it was experiencing first-hand that medical conversation is not sterile. What I mean is that it’s not always exactly like attending a formal Sunday tea party. This isn’t something that can truly be simulated in pre-clinical training. When we go to work, we deal with real, live human beings, and usually when they come to see us it’s not under the easiest of circumstances. Part of the job is speaking with patients who are anxious, angry, or frustrated. The reasons behind their attitudes, behaviours, and language choices are complex and multifactorial. It’s not our role to judge, and it’s key to understand that if a patient is upset, it’s usually not about you. To be clear, there is zero room for abuse of any sort, and although it can feel scary to do, you are never in the wrong for addressing it with your resident, preceptor, or the supports in place via the medical school. Having said that, there will be other situations that can challenge your patience, require great diplomacy, and drain your emotional energy reserves. Acknowledging that you are in one of these conversations is helpful for regulating your reaction and keeping a level head in the remainder of the interaction. Debriefing with the team can be beneficial to learn what other strategies team members use for challenging interactions. Lastly, recognizing that from a mental standpoint you may take some of your work home with you is also a valuable insight. It may be necessary for you to unwind a bit afterwards, and it’s okay to take time to do so. Finally, it’s helpful to appreciate that as medical students our job is not to have all of the answers (at least not yet). The one thing we can do, though, is to make sure that in every single encounter the person sitting across from us knows that we’re there to take good care of them. An empathy-based conversation recognizes and respects the humanity of our patients. By dedicating ourselves to this axiom, we can always put the wellbeing of our patients first, and no matter what our discipline, that’s a part of the Art of Medical Conversation worth talking about. By Kimberley Yuen, Meds '22

Backstory: Before I started medical school, my partner and I decided to do a backpacking trip for five months, which started in September 2017. Our first stop was India — we both had never been, and we were ready to explore this culturally rich, colourful and culinarily-exquisite country. We were three weeks into our time in India and we had just hopped off a train in Jaisalmer. Jaisalmer, nicknamed the “Golden City” is in the Thar Desert, which boasts touristy things like: “overnight desert getaway” and “camel desert adventure.” Being the India first-timers we were, we obviously had to try it out (but on a budget of course!). Naturally, we quickly booked one of the awesome-sounding overnight camel tours for the next day. The following morning, we were whisked up in a mid-2000s Jeep and were told we would be picking up another group. We didn’t know that another group would be joining us, but this also wasn’t the first time something like this happened to us. Turns out the group was a couple from Slovenia and coincidentally, a medical student and businessman (a Slovenian version of my partner and I). After 2 nights of sleeping on a blanket in the sand, with dung beetles crawling all over us and harsh winds blowing sand in our faces all night, an unforgettable and comical friendship was born. Side note: I would not recommend a budget overnight camel tour, no matter how extravagant it sounds. You definitely get what you pay for. At the time I met Ajda, she was a medical student in her last year in Slovenia. I recently asked her a few questions for this issue because I thought her perspective would be more than fitting. I also think it’s important to have conversations with other healthcare practitioners from around the world, both to learn from them and to gain some perspective. What is your current role? Currently I’m on maternity leave after which I will start rotating for an internship in Paediatrics. Why did you choose to go into medicine? Since I could remember I was interested in science, biology and the human body, especially genetics. So going to med school seemed a perfect decision to me. Honestly, I was more interested in Medicine in terms of science and not so much in becoming a doctor. I’m a doctor now but I would gladly go back to med school. I loved it. What is the process like in Slovenia? After finishing med school, which is six years, you have to rotate for six months. Rotation is mostly in emergency departments. After that, you can apply for a professional exam. If you pass, you are permitted to apply for specialization. Public tender for specializations is twice a year. Internships are given to candidates with the best score. Scores are composed of an interview, average grades, recommendation [letters] and extra points like published papers etc. The length of your internship depends on the specialty and can take from four to six years. At the end you have a specialty exam after which you finally become a licensed doctor and can practice medicine independently. What is the medical system like in Slovenia? We have a public health care system. We have mandatory insurance, however not all medical costs are covered by this programme, thus the majority [of people] also have additional insurance that covers full medical costs. What do you love most about medicine? That it’s alive. It can be unpredictable and challenging. And nothing is straightforward. Straightforward is easy and boring. But I was drawn to it because the physiology of the human body fascinates me. What is one piece of advice you have Be confident, you know more than you think you do. Still doubt yourself, you don’t know everything. What do you think could be improved in the medical system in Slovenia? Firstly, there should be more doctors. On an everyday basis it is often impossible to take time for your patients, to answer all their questions or to simply give them encouraging or kind words… you are just too worn out. A big problem is also the waiting periods to get [in] to [see] specialists. So, I guess the capacity on all levels is a big issue In Slovenia. |

In This Issue:

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed