|

Interviewed by Kimberley Yuen, Meds '22 I decided to interview some of my Black peers that I know are doing very cool and amazing things. They are creators, doers, and inspiring people. I think it's always important to remember the world outside of medicine, and I hope these interviews showcase their talent, provide you with some perspective, and that you will become as inspired by them as I am. We must begin/continue supporting Black/BIPOC creators and doers. Here is the second interview! Graphic by Kiera Liblik, Meds '23 Meet Kwazzi! How's it going? My name is Kwazzi. I'm a rapper, producer and songwriter from Toronto. Kwazzi (pronounced: kwa-zay) is my real name and stage name. My name means "Prince born on Sunday". I however, was born on a Tuesday, even though I was supposed to be here on Sunday. I've been doing music for 10 years now and have never looked back. What challenges or barriers do you face in your space and how do you overcome them? Aside from Covid-19 completely destroying the event/entertainment industry for artists like myself? Truthfully, a lot of the barriers come from within. Sometimes people tend to think that music is fairly easy, when really, it's quite stressful. The pressure you can put on yourself to be perfect creates imperfections. Writer's block is like an unruly child you're trying to keep under control, while inspiration sometimes is seldom found. For me, I like to distract myself. Let out my inner child. Go out for walks or drives, read a book, play video games, catch up on shows. The bigger issue comes when the distractions take over too much. You need to have a balance and that's hard to do, since we've all been confined to our houses for so long. Other than that, the only other big challenge is breaking out of the Canadian music scene. Unfortunately, Canada doesn't really support its local artists until they get noticed by the American population. Sad, but true. Where do you see the direction of your work in the future? In the direction of stability. I want to be at a point where providing for myself and those around me isn't an issue, but even more so, I'm able to put them in positions where they can provide for themselves. It might be the typical thing to say, but it's the truth. That way, God forbid this type of pandemic ever happens again, I know that no matter what, we're good and in that same vein, I could even help those who aren't in the same position. Who inspires you? Oh, shoot. A few people! My parents... actually, my whole family is inspirational. Malcolm X, my favourite artists, musical and otherwise. My girlfriend is pretty dang inspiring and my friends, too. Those around me or whom I've grown up with that have really made a way for themselves, you know? For all of these people, I see the work they put in to get where they got or to where they're trying to go and it makes me check myself. It makes me want to work harder and I love that. This issue is centered around Black Lives Matter with the aim of amplifying Black voices. Are there any thoughts you would like to share regarding BLM? It's beautiful and it's sad at the same time. I wrote a long letter to no one in particular, just a letter where I vent about everything that is and was going on. It's called Thinking Out Loud From A Place Of Hurt. I eluded to it on my Instagram, but never posted it anywhere. Here is the gist of it: I'll start by saying I know this isn't everyone, trust me, I know. Just remember that these are my thoughts. See, I believe in the movement, but as a brown skinned man in this world, I've noticed a pattern. A trend, really. It's hard for me to believe in these things, well - moreso the people surrounding the movement because of this pattern. I hate being this cynical, however, from where I am sitting, it seems like there are more people who support us because it's trending, rather than support us because we, too, are human beings with rights. All the anger and disgust you would see early on in social media posts - where did your passion go? It's as if people have hit this feeling of "meh, I'm over it" and then went back to their lives. Why? We can't be done with it all. We can't be over it. This is our life. So this trendy support that happens literally every year, for me, it's not a rerun I like watching. I feel like if we all truly began trying to learn about one another learning about each other’s history and struggles… If we all "stayed woke" together, as one people, at all times, even when it gets hard, then that could begin the changing of integrated mindsets some people have. I'm talking about the overall ignorance passed down through generations and the blatant subliminal messaging in the media that continues to portray brown-skinned men and women in a negative light. A lot of people believe what they see and hear, especially from the news or family members, to be true. If you're only ever exposed to the portrait that has been painted of us, you're more than likely to adopt the same thoughts and principles about us. Anyways, only when mindsets begin to change, then that can begin breaking the system, our system, which was created to push some people ahead and keep others behind. Just look at how young kids interact with each other. When kids play with other kids, they only see another kid; someone just like them. No more, no less. That is what we need to go back to. Anything else you would like to share?

You can follow me on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, everything. On all streaming platforms if you search "Kwazzi", you'll find me. You can follow me on Instagram @therealkwazzi, I'm like an active Casper on there haha. I recently put out an EP which was written, produced, mixed; everything was done by me. It's called Kwarantine, which is a play off my name and inspired by the quarantine. I'm also working on an album! It's dedicated to the wonderful working class people of this world, but really it's relatable for everyone. There’s no date on it yet, but I'll definitely post about it when the time comes. So, yeah, take a listen to my music, see if I fit your vibe and if I do, go ahead and follow me. I thank you for your support!

0 Comments

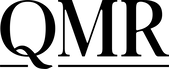

AuthorJessica Nguyen and Sarenna Lalani | Queen's University School of Medicine, 2023 Dr. Mala Joneja is an Associate Professor and the Division Chair for the Rheumatology Division at Queen’s University. She is also the Diversity and Equity Director at Queen’s, so we thought it would be a fitting and unique opportunity to interview and hear from her for this special issue of Queen’s Medical Review. We learned more about what is going on behind the scenes to address issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Queen’s, as well as how Dr. Joneja thinks medical learners can provide allyship to Black students, Indigenous students, and people of colour.

What are some of the projects you are currently working on? Currently, I am working with Dr. Philpott to put a plan for EDI (Equity, Diversity and Inclusion) in place for the entire faculty. That’s the big direction I’m going in. With respect to specific things I’m working on right now, I’m working with the admissions committee to help support any learners that are brought in through underrepresented routes. I’m working with the Faculty of Health Sciences Professional Development office on the Summer Reads Anti-Racism Program, where we go through a reading every Thursday morning related to anti-racism. I started a portal for medical students and residents, where they can anonymously report issues of racism or discrimination. I’m starting an interest group for residents and post-graduate trainees in equity, diversity, and inclusion, and I am hoping this will give the residents a safe space to talk about issues that occur. And I’m working on a new diversity statement from the School of Medicine.

What do you think is the physician's role in the Black Lives Matter movement? I think the first step for faculty and students would be to acknowledge that there are inequities. We pride ourselves on being a profession that provides compassionate and excellent care to everyone, no one is treated differently. And I think it’s time to acknowledge that there are inequities and there is a lot of literature on that no matter what specialty a medical student is interested in, and no matter what field a medical faculty is a part of - they’ll find literature on inequity, and I think understanding and acknowledging that is the first step. I think as physicians, in looking after Black people that are their patients, or teaching Black medical students, I think it’s really important that we really see who the individual is, and what being Black has meant for their background, their history, and their journey… In the case of the patient, looking after their overall health. And in the case of the student, looking at their career trajectory and mentoring them. How do you think medical students and faculty can contribute to improving equity in healthcare for BIPOC? It requires a process of inquiry, and curiosity, and compassion. Inquiring about one’s experience in a compassionate way, taking the time. One of the biggest barriers is that we don’t have time to spend communicating and learning about either our students or our patients as people. But it makes a huge difference to their health, for patients, and to the education for students. So it is a skill that I think medical students can learn. How do you quickly or efficiently find out what’s meaningful to the person about their situation? And how do you do that in a compassionate way? It’s something that I don’t think comes easy but with practice can happen. What is the most memorable or valuable piece of advice you were given when you were in medical school?

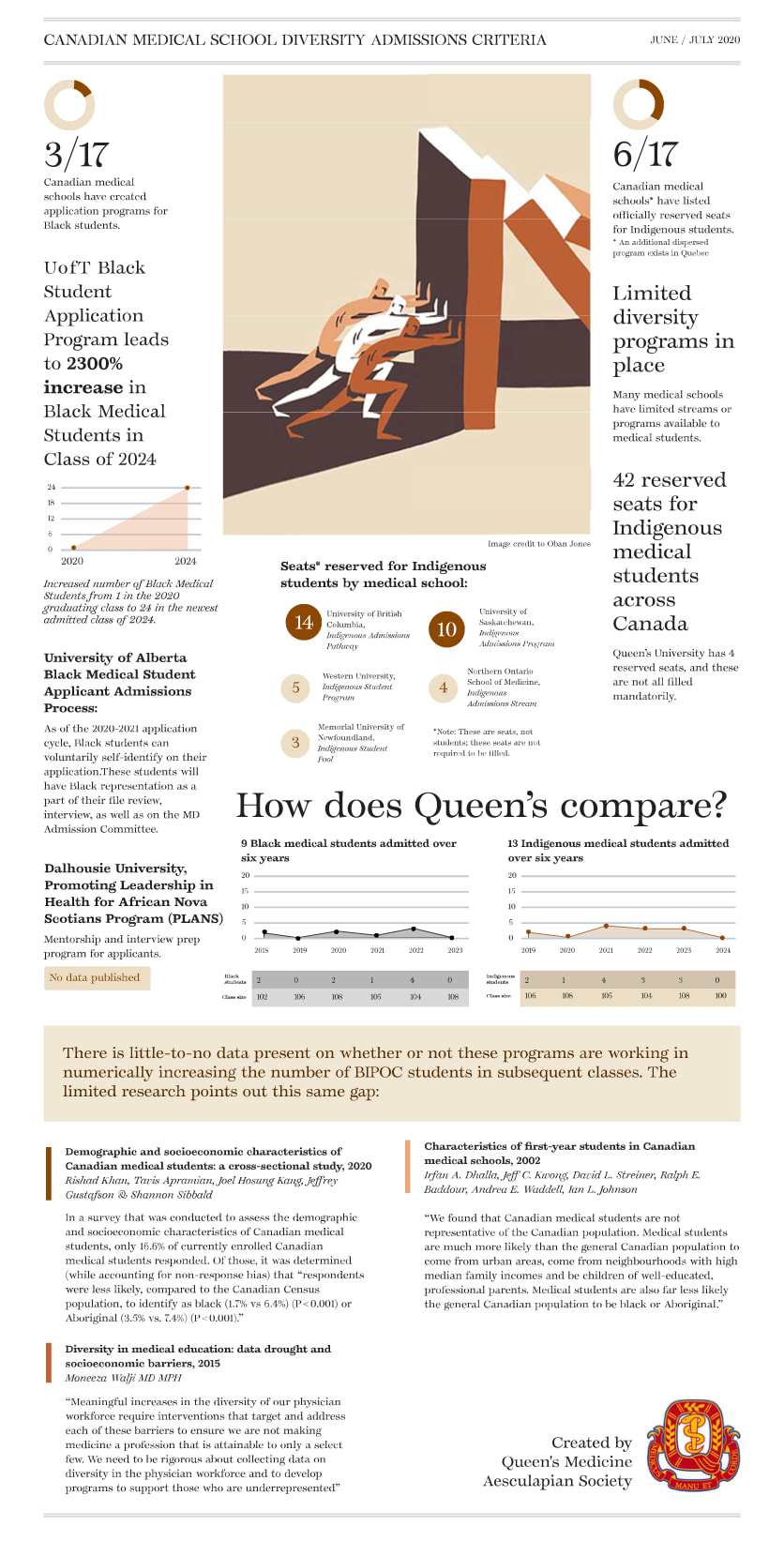

I think the most valuable message that I got was not to underestimate yourself and what you can do. And to be honest it’s those people, the leaders and the mentors that have seen some potential in me that I didn’t see for myself, that really helped me keep going and move forward. So don’t underestimate yourself or what you’re capable of. PublisherQueen's Medicine Aesculapian Society ContributorsDanny Jomaa, Sabreena Lawal, Anthony Li, Connor Weyell, Ayla Raabis, Palika Kohli, Christine Moon, Shakira Brathwaite Infographic Design Moe Kohli Introduction AuthorSarenna Lalani | Queen's University School of Medicine, Class of 2023 When the repeated, systemic and painful injustices against the Black community came into the limelight this past spring, it was not only police brutality that was revealed. Inequities were discovered within various facets of life, medicine included. Many were inspired to reflect on their own biases and brainstorm the actions they could take within their own lives to demonstrate allyship. Simultaneously, however, groups of individuals wanting to change the system emerged. In our QMed community, one such group formed and took action.  Credit: Moe Kohli Credit: Moe Kohli On July 1st, 2020 the Aesculapian Society's "Report and Demands to the School of Medicine Admission Committee" was released. Highlighting inequities in the medical school admissions process and thoughtfully framing calls to action for increasing diversity in Queen's Medicine, the report synchronously informs and inspires readers alike. The document also includes steps that outline the implementation of each demand and a thought-provoking infographic elucidating diversity concerns in medical school admissions processes across Canada. Definitely a worthwhile read for medical students, faculty and administrators, both here at Queen's and abroad.

AuthorKimberley Yuen | Queen's University School of Medicine, Class of 2022 I decided to interview some of my Black peers that I know are doing very cool and amazing things. They are creators, doers, and inspiring people. I think it's always important to remember the world outside of medicine, and I hope these interviews showcase their talent, provide you with some perspective, and that you will become as inspired by them as I am. We must begin/continue supporting Black/BIPOC creators and doers. Here is the first interview! Meet Aileen Agada! I had the pleasure of getting to know Aileen in her first year of university from being her Residence Life Don. Read more about Aileen’s journey as an entrepreneur and her ground-breaking startup that aims to change the hair care industry for Black women. Aileen is also a part of GreenHouse’s Innovators in Residence Program at St. Paul’s University College where she received the Social Impact Fund in July 2019. She has also been chosen as one of only 36 young entrepreneurs from across Canada to participate in the 2020 Next36 program, which is a Toronto-based incubator that supports entrepreneurs. Who are you and what do you do? My name is Aileen Chinwe Agada and I’m currently an engineering student at the University of Waterloo. After working in a variety of companies in Canada and spending some time in Belgium; I decided to tackle new challenges in the hair care industry with my startup, BeBlended! As a founder, I attribute my success to my hard work, supportive network, and active Christian faith. When I’m not working on BeBlended or studying engineering things, you can find me kayaking, mentoring women within my community, and spending time with friends and family. What is BeBlended and how did it start? BeBlended is essentially a software company tailored towards Black hairstylists. We produce tools that enable them to work more efficiently as Black hairstylists, and we’re also a marketplace that connects Black women to hairstylists worldwide. Basically, we want to create accessible haircare services for Black women globally. The idea for BeBlended started when I was on a co-op term in Ottawa and needed to get my hair done. I walked into about 15 different hair salons and all of them unfortunately turned me away. I thought “why is this a problem that I’m experiencing?” and it turned out to be because of my hair texture - a lot of hairstylists weren’t familiar with my hair texture. I quickly realized that I wasn’t the only one experiencing this and when I asked around to find a hairstylist, it was always the same answer – it was usually a friend of a friend, of a sister of a sister of an aunt somewhere that does their hair. What challenges or barriers do you face in your space and how do you overcome them? When it comes to challenges and barriers, honestly, I would say when it comes to innovating in the beauty industry (beauty tech), there’s somewhat a stigma because it’s beauty and cosmetics. People think that beauty and cosmetics can’t evolve in the technical sense, but I believe it can. However, given the feedback from our users and from people that sign up on our mailing lists, a lot of people are starting to understand that this is a huge problem and the barriers are starting to recede. I think the entry point to enter the industry is easier now and people are starting to understand what beauty tech is. I would say believing in my idea and knowing that this is a problem (aka doing the research and backing it up with data) is how I over come barriers. In the ideation stages of BeBlended, it was very hard to find Canadian data on Black women and their beauty habits, purchases, etc., and even with larger well-known databases, I still wasn’t able to find anything relevant to my target market. So, I went out on my own to gather data and created my own database. Now we have over 700 data points from Black women across Ontario that have said all the claims that we’re stating. 90% of Black women are turned away from hair salons, like that’s a fact. It’s one thing to talk about a problem, but it’s a different story when you can back it up with data. Because we have received the data, the data speaks for itself and is helping me get through these barriers. Now I just need to keep powering through start-up life pretty much! What are you currently working on? Currently we’re preparing to relaunch the website with Covid restrictions and working on onboarding hairstylists. Check us out at www.beblended.ca Where do you see the direction of your work in the future? As I mentioned, BeBlended is also a marketplace that connects Black women to hairstyles worldwide. A key part to pay attention to is worldwide – we’re not just meant to stay in Canada, we are trying to grow globally! In the future, I’m planning to work on BeBlended full time and potentially do a Master’s degree part time in business entrepreneurship and technology. I’m excited to grow with our team and user base and other funding opportunities that we’ll get a hold of. Do you want to share any of your current thoughts regarding the Black Lives Matter movement? I would say I’m just happy people are beginning to wake up to see the injustice in a lot of different industries towards the Black community. I’m happy people are becoming more aware. Unfortunately, it happened through the killing of George Floyd but I’m happy people are beginning to see the problems that they may have never seen before if it weren’t for this. I’m confident and hopeful that people will start moving forward, be more inclusive, see life from a different perspective, and understand the limitations put on the Black community. I’m positive that things will change. If you want to read more about Aileen and follow her journey with BeBlended, check out the links below!

Website: www.beblended.ca Social media:

Articles:

Videos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3NCzrQi6PFs Podcasts: AuthorMatt Gynn | Queen's Medicine Class of 2022 Race and racism are two intertwined topics that have been brought to the forefront of medicine. It is important to acknowledge that there have been systemic biases for years in patient data collection. However, there are some unique circumstances where factoring in race may be appropriate for the foreseeable future. I present a few referenced examples that illustrate a potential role for race in medicine moving forward. I am by no means an expert, but I hope to shed light on reasons why to include and not include race in the context of our future patients. Why is race/ethnicity different than any other risk factor?All medical information is not created equally. Incorrectly understanding the symptoms or treatments and a racial/ethnic correlation of a disease have very different outcomes. Mistakenly associating cough with streptococcal pharyngitis affects all patients on an even playing field. Incorrectly thinking about Black ancestry in the context of a gonorrheal infection may implicitly change your perception of the patient and/or the disease. As such, inappropriately thinking about Black ancestry does not affect all patients equally. These distinctions may not apply to every disease, but when race/ethnicity (or any demographic information) is listed as a risk factor, it’s important we critically analyze the actual evidence and utility of including it moving forward. Arguments For Including Race - Example 1: Sickle Cell DiseaseThe primary argument for including race/ethnicity is its correlation with genetics. Genetics affect our health and set baseline probabilities for acquiring different diseases in our lifetimes. There are historical reasons as to why there are differences among ethnically diverse groups (which I won’t go into), but certain genetic variants are more common depending on your ancestry. Let’s use the example of sickle cell disease. In the U.S., the incidence of the sickle cell trait (one copy of the sickle cell hemoglobin variant) is 73.1 per 1,000 among Black newborns, 6.9 per 1,000 among Hispanic newborns, 2.2 per 1,000 among Asian, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander newborns, and 3.0 per 1,000 among White newborns[1]. So simply by having Black ancestry, the baseline probability of being born with sickle cell disease (two copies of the sickle cell hemoglobin variant) is roughly 1 in 365 whereas for Hispanic newborns it’s 1 in 16,300 (an almost 45x difference!)[1]. Unfortunately, we do not have rapid tests that can immediately sequence and interpret each patient’s genetic code. The big insights we have into our patient’s genetics are through their family history and, in a broader sense, their ancestry. Keep in mind that knowing one’s family history may be a luxury every patient might not have, so a patient’s race might be the only clue to any potential underlying genetic predispositions to specific diseases. However, maybe we should avoid the use of colour labels when referencing race/ethnicity. Using the sickle-cell example above, would it be more appropriate to use Sub-Saharan African ancestry in place of Black ancestry to remove the direct reference to skin colour? Arguments Against Including Race - Example 2: COVID-19The primary argument for excluding race is the inherent association with systemic racism and oppression. When we slap a race/ethnicity label on a disease, is it because there are real differences in the prevalence of genetic variations among different races? Or is it the product of an upstream chain of events that create inequality in our society? I want to present this quote from an article published in the very prestigious journal The Lancet on May 2nd, 2020. The title of the article is Ethnicity and COVID-19: an urgent public health research priority. Ethnic classification systems have limitations but have been used to explore genetic and other population differences. Individuals from different ethnic backgrounds vary in behaviours, comorbidities, immune profiles, and risk of infection, as exemplified by the increased morbidity and mortality in black and minority ethnic (BME) communities in previous pandemics [2]. Consider the first descriptor used to describe why BME communities have increased morbidity and mortality: behaviours. This word places blame on the BME community and by including the word at the front of the list it implicitly suggests these “behaviours” are the most likely explanation for the differences in mortality and morbidity. Essentially, this paragraph argues that these “[cultural] behaviours,” among other variables, warrant race/ethnicity being a risk factor for COVID-19 without the proper consideration for upstream variables that lead to differences in healthcare outcomes [2]. In another article published on May 7th, 2020 the data from the NHS in the UK is synthesized and the authors conclude: People from Asian and black groups are at markedly increased risk of in-hospital death from COVID-19, and contrary to some prior speculation this is only partially attributable to pre-existing clinical risk factors or deprivation; further research into the drivers of this association is therefore urgently required [3]. Yet again, a 2020 article is ignoring the systemic issues and suggesting race is an appropriate risk factor for COVID-19. Even in a meta-analysis of COVID patients published on June 3rd, 2020 Black patients are reported to have an increased risk of both infection and worse clinical outcomes [4]. I have been able to find a New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) article that says there are no health disparities between White people and Black people once socioeconomic factors are adjusted for, however, these types of reports are in the minority [5]. COVID-19 highlights a problem with how clinicians like to collect data and publish. Medicine is very outcome-based; you take a cohort of patients and run advanced statistics to see what must explain the differences. I do not think this approach can adjust for systemic racism, but the “statistics say the differences are real” even after socioeconomic differences are adjusted for… Furthermore, why are researchers so interested in determining which races are more susceptible to COVID-19? Race/ethnicity should not change how these patients are treated in the acute care setting. In this setting, patients should be worked up and investigated based on their symptom profile, not their race/ethnicity. Further, assuming race is the inciting factor rather than racism, systemic oppression, and flawed institutions limits our ability to tackle health inequities appropriately. By putting a label on BME communities very early in the COVID-19 pandemic, some clinicians will forever have their perceptions of the specific racial/ethnic communities altered. This label is unfair to these populations of patients and perpetuates systemic problems. Instead of starting at the outcome and working backwards, we should consider starting at the beginning (the genetics) and working forward before officially applying this label to any group of people. It’s more equitable to assume that the genetic variability among the ACE2 receptor (the receptor the COVID-19 virus binds to) is equal among all races [6]. If research can prove that a specific genetic variation is more prevalent in a defined population then perhaps it is appropriate to consider incorporating race/ethnicity in a relevant disease context. Arguments For Including Race - Example 3: Cystic Fibrosis MutationsCystic fibrosis (CF) is a disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene. It is more prevalent among the white population with a prevalence of ≈ 1 in 2500 among Ashkenazi Jewish and non-Hispanic White people, 1 in 15,000 among Black people, 1 in 35,000 among Asian people, and 1 in 10,900 among Native American people [7]. Even when disease is reported to be more common among the “majority”, it is important to still have some skepticism. Are these differences due to real genetic differences or better access to health care? In the case of CF, research has indeed specifically addressed this question and shown CF mutations are less common in minority populations [7]. Arguments Against Including Race - Example 4: HIV Infection RatesIn 1988, the NEJM published an article that stated HIV-seropositivity rates for patients attending STI clinics were higher among Black people than white people [8]. Again, I am no expert (and am open to learning more if I am incorrect), but I was not able to find any research that has shown a genetic variation of either the HLA receptors or CD4 receptors that increases the risk of HIV among the Black population. Certainly, if this research exists, it was not known in 1988. Yet the stigma and damage that was done by labelling being Black as a risk factor for an infectious disease is irreversible and unnecessary. Arguments For Including Race - Example 5: Warfarin DosingThe inclusion of race in medicine should be under the pretenses that it can improve outcomes for our patients. So far, I have outlined mainly disease statistics that can be explained by the frequency of genetic variants in specific populations. These types of statistics are important in the framework of primary care when we want to either prevent disease or catch it as early as possible. What about acute care? Once there is a constellation of symptoms in front of us, is there any need to consider race? The assumptive answer to this question should always be no, but there are some instances where race can effectively guide treatment. In 2015, hematologists showed that ethnicity-based stratification of warfarin dosing improved dose prediction in both White and Black patients [9]. Warfarin is a drug with a very specific therapeutic window that must be monitored frequently, thus accurate dosing is important for the patient [10]. The explanation for these race-based differences is from previous studies that show different distributions of the gene variants related to warfarin’s metabolism between White and Black people [9]. ConclusionI hope these examples highlight the importance of thinking about race with a critical lens moving forward. We can do unintentional damage by not thinking about race/ethnicity properly. If the reason race/ethnicity has historically been included can be traced back to systemic oppression, it should be excluded from medicine. At the same time, ignoring the unique circumstances where genetic differences are prevalent among specific ethnic groups also does our patients a disservice. There are many more examples of an inappropriate use of race in medicine published in this article by the NEJM for further reading. References

AuthorVincent Tang | University of Toronto, Class of 2021 I was born in Canada, but I didn’t grow up here. I spent most of my formative years growing up and being educated in the Southern United States. Where I lived, 90%+ of the student body was white and 95%+ of the teachers were white. As a young, gay, Chinese-Canadian/American boy trying his best to fit in, I remember being pigeonholed into being a “model minority”. I was “smart”. I was “good at math” and “hard-working”. These were characterizations I was quick to accept, because it seemed to me to be a requisite to building connections and making friends at the time.

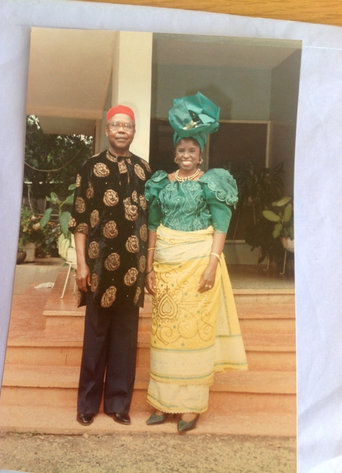

Over time, even though I was one of only a few people of colour in my schools, I began to make friends and find that sense of community that I yearned for after having been uprooted from what I knew as my home in Canada. But despite finding my place in this predominantly white community, I never felt like I belonged. I was often shamed for the lunches my mom would pack for me. Occasionally, my peers would yell racial epithets at me and gesture towards me with squinted and narrowed eyes. I was always reminded that my acceptance into these groups was precarious and conditional. But regardless of my own experiences with racism and discrimination, what I didn’t realize then was that, despite everything, I was being enculturated with the racism of white supremacy. When I learned social studies in middle and high school, I was reading textbooks approved by a government made up predominantly of white people and written by white authors. My only view into the “other” was through events such as the Civil War in the 1860s, where white people are portrayed as the saviours of slaves. I was constantly surrounded by white people, and so I had internalized what was “socially acceptable” from their point of view. When I began to transition from high school to university, I noticed that I felt more comfortable when I was surrounded by white people. I had begun to view people of colour, including other Asian and Chinese people, but especially Black and Indigenous people, with an innate heightened suspicion, based on how I saw my peers and my family interacting with them for years. Without me even knowing, white supremacy, anti-Black, and Indigenous racism had interwoven itself into every fibre of my being. The indoctrination of white supremacist ideologies is insidious and instills within us a certain set of beliefs and stereotypes that becomes tied to our identities. We begin to turn a blind eye to the prison-industrial complex and the policing and mass incarceration of Black people because it doesn’t directly impact us. We make excuses for our own biases by saying we cannot be racist because we have lots of racialized friends and they are all “good people”. When we watch yet another news story of the police shooting someone, of which the majority have been Black and Indigenous peoples, we begin to make rationalizations as to why the police committed those acts “in the name of public safety” and “law and order”. We never think to take a step back to question the origin of our beliefs and we learn to simply accept the world for how it is. Especially for people of colour, we think we can’t be racist or discriminatory towards others because of our own identities and our own experiences with racism – only to not realize that we use those justifications as excuses to absolve ourselves of doing the deeper work of being truly anti-racist. Medicine is a societal institution that likes to hold itself up as a progressive bastion of social change – at least to those inside its walls. But unfortunately, medicine is not immune to these tendencies – if anything, medicine serves as a perpetuator of the everyday stigmas and structural inequities that we so easily ignore. We learn that “being Black” is a risk factor, but the same clinicians we look up to don’t explain the why. They don’t explain how centuries of systemic discrimination, socioeconomic inequalities, and barriers to care contribute to the pathology we see. No one speaks about the history of experimentation on Black and Indigenous people as the foundations for our medical knowledge today. Social constructs are conflated with biological risk factors in teaching, in exams, and thus, in the way we approach the patients we see in our shadowing opportunities and clinical rotations. When schools attempt to make efforts to teach from an equity and justice lens, these concepts are taught as theories only, without any connection made to medicine and our clinical work. We’ll spend one hour talking about social justice and being culturally sensitive and three hours talking about medicine and science, only for the medicine and science to make up 100% of our examinations. And so, when we encounter the topics related to the social determinants of health again, we tune ourselves out, since these topics won’t help us on our exams. The social history is only emphasized in specialties that perceive themselves to play a significant role in SDOH, such as family medicine and psychiatry, but certainly it should also play a significant role in other specialties too. When we, as medical learners, encounter microaggressions or outright racism in our clinical work, we’re taught to be quiet about it, lest we be marked as unprofessional for speaking out. I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not perfect and that I still have lots of unlearning and learning to do. It’s taken years for me to work through my own biases regarding anti-Black and Indigenous racism, and it’s work that continues as I write this. When I feel myself getting defensive while having a conversation with someone or when I read or watch something, I have to take a step back and remember: this isn’t about me; this is an opportunity for me to learn and to continue to work on untangling the threads that have bound me and my thinking for so long. As medical students and future medical professionals, we have a professional and moral obligation to do this work, to educate ourselves, and to understand the violence that the medical community and society writ large has and continues to inflict on BIPOC communities. Medical institutions continue to ask BIPOC to do the work of educating their peers as to their own experiences, to continue to pay an emotional labour tax without the guarantee of any change. While we need to continue to amplify BIPOC voices, we cannot expect BIPOC to constantly educate us. The act of asking them to relive their own traumas day in and day out in a display for our own education is an act of racial violence. We must stop labelling ourselves as being “progressive” simply because we are in medicine and recognize that simply by being in this field, we inherently have accumulated metric tons of societal privilege and a history of discrimination and racism. As a profession entrusted with safeguarding the lives of others, we can no longer stay silent. The society we’ve lived in, some of us comfortably and some of us not, has regardless inflicted traumas on communities that stretch back generations. If we can sit back and accept that, it’s a sign that we have more work to do. Black Lives Matter. AuthorIku Nwosu | Queen's University School of Medicine, Class of 2022 “You have to tell the whole truth, the good and the bad, maybe some things that are uncomfortable for some people.” - John Lewis (1940-2020) I have never sat down and documented my experiences as a Black woman. I think this is partially because I, like many Black women, have dedicated a lot of time assimilating and distancing myself from tropes that are associated with my Blackness. Still, at times these tropes become labels that I cannot avoid. This concept of tropes – the “angry Black woman”, the “sassy Black woman”, and even the “strong Black woman” have lingered in my mind as well as all my interactions subconsciously for years. I certainly do not want my story to become part of any stereotypes or to be implicated as the experience of other Black women – perhaps another reason I have not written much of this down. However, individual experiences are qualitative evidence – they are valid and I hope they can contribute to learning especially within my personal circles. I named this piece Awakening because that is how my story begins and it is a recurring theme in snippets of my life so far. It begins the moment in my childhood where I realized being Black was different and to some people, “a big deal.” I became awake to it. I did not grow up initially thinking my skin colour was something of note. The people I loved and admired the most were Black. Some people were also Black or not Black – it was that simple. Just like any non-Black person does not grow up thinking their race is going to be this definitive aspect of their identity, I grew up the same. As a child, you are probably not thinking about how your race could impact your experience making friends, getting jobs, or even within public structures like health care and the criminal justice system. I was not awakened to this fact on one particular day of elementary school, but rather it was a compilation of what I saw in mass media and having other children comment on our differences. There were few Black characters or even Disney Princesses when I was young to dress up as in costumes. There has always been odd commentary when people try to dress up as characters that do not “look like them” - as if this really should matter. Suddenly, I was 7 years old and very aware of my Blackness. My story of awakening is also a story of untangling myself from my own anti-Blackness. I would describe myself as outspoken, social, and keen. I have always been keen when it came to academics but also keen to get to know people deeply and earn their respect. Still, I have always had this feeling that at the forefront of who I am is my race. I constantly feel like in each of my initial interactions with people, that I am dismantling stereotypes they may come in with – this may be a pessimistic approach, but I have always found it to be the safest. In light of the recent Black Lives Matter protests, I have come to realize how much of how I viewed myself was tainted by internalized racism. Imagine growing up and consuming content all the time that is covertly or overtly anti-Black. The same anti-Black content that non-Black people subconsciously internalize is what most Black people are also exposed to and internalize. Sebene Selassie, meditation teacher and author, described it like a form of “double consciousness”, surviving in an anti-Black world but also being a Black individual. Outside of historical fiction, Black people were more often portrayed in relation to gang and gun violence, as troublemakers in school, or as sidekicks lacking depth. Films like Akeelah and the Bee where a young Black girl from a poor background eventually wins the National Spelling Bee were constant replays because frankly, there was not much else remotely positive that centered young Black girls. Even in elementary school, I remember constantly watching the Black kids be treated as “the bad kids” and experiencing this at times myself. As discussed in Netflix’s Dear White People, you become scared of your own community and its potential for violence. Concurrently, you become scared of being perceived as violent or as the other negative tropes that are constantly shown in mass media. A survival tactic is to distance yourself so far from this so that you are non-threatening, can assimilate, and succeed – so I did this and have continued to do it until this point. My story of awakening includes recognizing the need for the Black role model – the feeling was palpable for me when a Black role model was in a space. Black role models have not been in short supply in my life. My parents are well-educated and self-employed business owners, my late maternal Grandfather was a well-loved physician and senator in Nigeria, I have physicians, engineers, nurses, teachers, and everything in between on both sides of my family. I think it showed throughout my life as I always knew and was often told how much potential I had and saw what I could achieve. Yet, there is something truly comical about being asked if I knew how to speak English while dressed in full professional attire at my Bed & Breakfast the morning of my Queen’s Medicine interview - my Grandfather himself gave a full speech, in English, to a class of medicine graduates in Nigeria in 1989. My Grandmother was also an English teacher and eventually a principal. Microaggressions like this are painful because they reveal to how much (often white) people do not understand the state of knowledge in BIPOC communities around the world. The same ignorance is riddled throughout anti-immigrant rhetoric, despite Canada being built through settlers with the ideology of colonialism, and this hatred is rarely directed towards white immigrant populations. Black role models; My parents, Chioma Emezie-Nwosu and Zubbi Nwosu at their matriculation and Bachelor’s degree convocation respectively. Both went on to pursue Master’s degress in the U.K. Black role models however, were in short supply in all my public institutions. I had three Black teachers from Kindergarten to Grade 12 and I can name them: Mrs. Findlay, grade 7, Mr. Kouadio, grade 8, and Mrs. Brown, grade 12. Not coincidently, these teachers are also among the ones who I never felt doubted my abilities. Throughout school I often found my teachers described me as excelling in a way that seemed to surprise them – it was never clear to me why. I do not think my elementary school had a single Black teacher on staff the entire time I was there. I mention these teachers because yes, having Black teachers did make a difference to me. Seeing them always made me feel safer and my presence among my peers felt more normalized. It is challenging to describe the feeling of being a child or teenager, and just instantly feeling a bit more like you belong. This is the power of representation – a privilege that many do not recognize they have. Imagine yourself in school and never seeing a teacher that looked like you – not even in the hallways - not the most comfortable reality to picture. Yet, this is the norm for many Black children growing up in Canada. Even in the “cultural mosaic” that was Mississauga for me, the lack of explicitly Black representation or even Black celebration in our education was notable.

My story of awakening continued in higher education where I have discovered in short, the existence of ongoing institutional racism and the ignorance of students, faculty, and community members to this fact. My undergraduate experience can be summarized by two main realizations. The first being that the war on drugs is really a war on poor and racialized communities as I have never seen more drugs so openly used as I have within “elite” university populations. As someone who grew up seeing drug use only portrayed in racialized communities and perhaps in elite corporate culture, its normality in everyday life was astounding. This alongside the copious amounts of binge-drinking that many of my peers attested to participating in since early in high school (I cannot relate). The second was that dating culture is certainly not the same experience for Black women. A lot of my interactions at outings consist of filtering out fetishization from genuine interest or having people suggest only Black men towards me because they assumed only those men would have an interest in me. I can say that although I attend a heavily white institution for medical school, Queen’s, I truly am surrounded by the most open-minded and inclusive friends – the majority of whom are BIPOC. It was a disheartening experience to learn within the first two months at Queen’s Medicine that from 1918 to 1965, my school had a formal ban on Black medical students[1]. A ban that was still technically in documentation until it was formally repealed in 2018 – the year I started at Queen’s. At one point it felt like everyone I knew had felt the need to send or tag me in articles about this – a constant reminder of the mistakes of the institution I would be attending for four years. I always ask myself, when Queen’s put this ban on Black medical students into effect, where was the public outrage? Where was the support for these students from all the other medical institutions in our country that are supposedly faultless? I am curious what is yet to be revealed about the racist practices of institutions in their history. In my eyes, it was obvious that the intergenerational effect of this was still occurring at Queen’s due to the blatant lack of Black medical students. In March of this year, I was grateful to attend the historic inaugural meeting for the Black Medical Students’ Association of Canada in Toronto. Being in a room full of people in your field who look like you is a privilege that many Black medical students do not have every day. It was invigorating and rejuvenating of many things I believe about representation that I felt like I was starting to lose sight of. The family we have across Canada is undeniable and listening to their experiences, some being the only Black student in their class, saddened me. Through my work as Co-Director of Communications hereafter, I have further disentangled some of the internalized racism I had towards the knowledge and potential of Black students. Many believe Black students are not in medical school because they lack merit and for a time, I bought into this as well. However, I can confidently say now that meritocracy is an illusion that benefits those that life already favours with opportunities and who do not experience systemic oppression. We need our system to reward individuals with consideration of the various backgrounds, context, and circumstances that result in the advantages or disadvantages applicants may face. Now let’s talk about silence. Institutional racism also became evident to me when a Dermatology lecture could start with “I’ve pretty much for all of the slides given examples of Caucasian skin. […] once we move through today and move forwards into the months and hopefully years ahead, hopefully I’ll be able to come and I will bring you other skin types.” Spoiler: there has never been a session during our Dermatology block or any time in the upcoming years of medical school scheduled for lectures on Skin of Colour– this was an empty promise. A start like this would have gone unquestioned if not the for the vocal advocacy of myself, one of few Black students in our medical school. I hope in response to recent calls to allyship, others will feel comfortable advocating loudly alongside me to direct curricular change. It is also important for institutions to act on the saying, “nothing about us, without us.” The desire and act of not consulting Black stakeholders is rooted in white supremacy and superiority in our culture. Seeing Black people as the most knowledgeable makes people uncomfortable and it should not when you are talking about changes that impact the Black experience. It is eye-opening to see classmates and future physicians who are normally vocal about their own life affairs and perhaps select issues like climate change or feminism, be completely silent when it comes to advocating for Black lives. It is in seeing people post and like content about #MedBikini who never did the same for the Black Lives Matter movement even though “professionalism” biases affect Black women in even greater magnitudes (many of whom would not feel comfortable sharing a bikini photo publicly out of these fears). This awakened me to a simple realization: receiving a medical school acceptance letter does not guarantee any individual is empathetic. In many ways, I have realized that people in medicine are among those with the largest egos. Many forget that medicine is a public service funded by the federal government, inherently political, and that these deceivingly “soft” social issues are actually blatant health concerns for the people you will treat. Furthermore, people in medicine are among those who may never have their ego checked again due to how society holds us on a pedestal. In June, Toronto Board of Health declared anti-Black racism a public health crisis and this sentiment has been shared among physicians and health organizations internationally. Yet, numerous medical students, the future of this profession, think that ignoring this issue is completely okay. Thank you to those who have acted otherwise and believe that participating in this movement and becoming an ally hereafter is part of an ethical obligation we have as a part of medicine. It is important to do so without projecting your own white guilt onto Black individuals who actually live with racism on a daily basis. All of this is not about white guilt, it’s about actions to centre on and change the experiences of Black people. My inbox is always open to those who are still finding their way and may need a hand. My story of awakening is also a story of acceptance. Acceptance of my community and all their potential despite others’ attempts to claim otherwise. And acceptance of myself, love for who I am, and all that I am capable of doing for the good fight. |

|||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed